World Refugee Day (June 20) honors those who leave everything behind to escape war, persecution, or terror. This day celebrates the courage and resilience of refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons, stateless persons, and returnees, as the plight of those fleeing conflict is often met with overwhelming uncertainty and assault on human rights.

World Refugee Day (June 20) honors those who leave everything behind to escape war, persecution, or terror. This day celebrates the courage and resilience of refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons, stateless persons, and returnees, as the plight of those fleeing conflict is often met with overwhelming uncertainty and assault on human rights.

Tag: migration

Spring Simulated Shelves

Browse our February and March 2020 releases in Anthropology, Archaeology/Heritage Studies, History, Memory Studies, and Mobility Studies and see what’s new in paperback.

Leyla and Eman

Connecting German-Turkish and Syrian-Turkish Stories

By SUSAN BETH ROTTMANN, Özyeğin University

A Series on a Series: Part I

Interview with Series Editor Sam Beck, Romani Studies

Did you know Berghahn Books has over one hundred series? Covering a wide range of subjects and areas, Berghahn’s series list continues to grow as new interventions and trends in scholarship are made.

Continue reading “A Series on a Series: Part I”Are There Sustainable Cities in the Arctic?

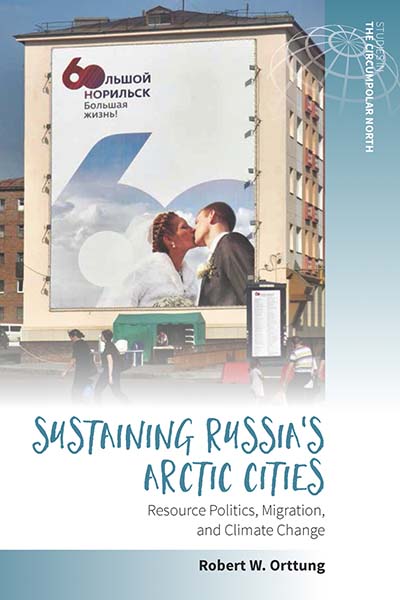

by Robert Orttung

by Robert Orttung

Robert Orttung is the author of Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities: Resource Politics, Migration, and Climate Change, which will be available in paperback in 2018. We’re offering 25% off the paperback with code ORT427 on our website.

More than four million people live in the Arctic, but so far few scholars have addressed urban conditions there. In fact, most people living in the Arctic reside in cities. Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities: Resource Politics, Migration, and Climate Change is one of the first to try to examine how sustainable these cities are.

The edited volume Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities grew out of a multi-disciplinary and multi-national team of scholars interested in the Arctic. The idea to focus on cities came from one of the book’s contributors, Nikolay Shiklomanov, during a meeting of faculty with an interest in the Arctic at George Washington University. Participants represented both natural scientists who study permafrost and climate change, and social scientists interested in migration and energy development. Cities proved to be the meeting ground where all of our interests converged. As resource extraction continues in the Arctic, more workers are moving to the region and building more infrastructure there. However, the extraction and subsequent combustion of fossil fuels leads to warming in many parts of the Arctic, typically at a rate much faster than on other parts of the planet.

The focus of this book is on Russian cities in the Arctic because Russia has gone the farthest of the Arctic countries in developing urban space in the far north. Stalin built large cities in the region as did subsequent Soviet leaders in an effort to develop the rich resources found there.

The book addresses the question of how humans can live in the Arctic while having minimal impact on the environment. There are no easy answers, so the various chapters consider the history of Arctic development in the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia, policy-making processes for the Arctic in Moscow, the administration of specific Arctic cities, the nature of the workers who make their living in the Arctic, the prospects for land and sea transportation in the region, and what we know about the future climate.

This book is the first of several that we hope to publish in an on-going research project. Currently, Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities serves as a foundation for developing an Arctic Urban Sustainability Index. This index will examine five types of variables – economic, social, environmental, governance and planning. The Index is in its early stages and we are reporting progress over time at our project website. The most recent publications include two reports in the 2017 Arctic Yearbook. The project has the support of the National Science Foundation Partnerships for International Research and Education.

We hope that readers from a wide variety of disciplines and perspectives will find the book useful in starting to think more serious about cities in the Arctic. Ultimately, we hope that this research program will lead to useful advice for mayors and other Arctic policy makers as they try to improve lives for the citizens of Arctic cities.

Robert W. Orttung is the research director for the George Washington University Sustainability Collaborative. He is also an associate research professor at GW’s Elliott School of International Affairs. He has written and edited numerous books on Russia and energy politics.

Promoting ‘self-reliance’ for refugees: what does it really mean?

The following is a post by Naohiko Omata, author of The Myth of Self-Reliance: Economic Lives Inside a Liberian Refugee Camp.

Promotion of ‘self-reliance’ for refugees has occupied a central seat in the policy arena of the international refugee regime in recent years. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) broadly defines self-reliance as ‘the social and economic ability of an individual, a household or a community to meet essential needs in a sustainable manner’. Its guiding philosophy can be summarised as: refugees have the skills, capacity and agency to stand on their own and be able to sustain themselves without depending on external humanitarian aid. This concept has been universally embraced by policy-makers and aid agencies and has now become an increasingly visible part in refugee assistance and protection programmes worldwide.

But on the ground, what does it really mean for refugees to attain self-reliance?

While many policies have rhetorically committed to the importance of ‘helping refugees help themselves’, some fundamental questions remain unanswered.

First, do refugees have enabling conditions to achieve self-reliance? Currently, many refugees in the Global South are unable to fully exercise their right to work and to move freely due to regulations by their host governments. These impediments can severely constrain refugees’ capacity to construct meaningful livelihoods and limit their access to commercial markets. Under these restrictions, is it sensible to assume that refugees can attain self-reliance regardless of how industrious and ingenious they are?

Next, how do we determine whether refugees have achieved self-reliance? Despite its extensive promotion, there are to date no universally agreed systematic and rigorous criteria for measuring refugees’ self-reliance. Instead of using objective benchmarks, UNHCR often perceives refugees as self-reliant when they live without external assistance. Is the situation in which refugees living without aid a plausible indicator of ‘meeting their basic needs in a sustainable manner’, as defined by UNHCR?

Most importantly, for whom is refugees’ self-reliance being promoted? In theory, nurturing refugees’ self-reliance should entail a strategic shift from traditional relief aid to development-oriented support and the provision of enabling conditions for refugees to establish gainful livelihoods. Yet this is not happening in the field. Meanwhile, UNHCR and donor states usually start decreasing assistance for refugees while promoting refugees’ self-reliance. Is refugees’ self-reliance meant to empower refugees’ economic capacities or to justify cutting down aid for refugee populations?

My authored book, The Myth of Self-Reliance, has explored these important but unsolved questions through a study of Buduburam refugee camp in Ghana. This Liberian refugee camp has been commended by UNHCR as an exemplary ‘self-reliant’ model in which refugees were sustaining themselves through robust businesses with little donor support. The UN refugee agency even boasted that the organization had facilitated their economic success by gradually withdrawing its assistance over the period of exile.

The book challenges the reputation of Buduburam refugee camp as a successful model for self-reliance and sheds light on considerable economic inequality between refugee households. Both qualitative and quantitative data reveal that a key livelihood resource for refugees in Buduburam was not their commercial activities but their access to overseas remittances, which had nothing to do with UNHCR’s initiatives to foster refugees’ self-reliance by withdrawing aid. While refugees who were receiving remittances were able to satisfy their basic day-to-day needs, those who had no connections to the diaspora were deeply impoverished.

There is increasing support for the idea that refugees are active and capable players with ingenuity and resilience. I agree wholeheartedly with this view in principle. However, it is irresponsible to assume that this can entirely replace the need for humanitarian aid and protection, in the absence of an enabling environment and adequate resources. Over-emphasis on the resilience, agency and capacity of refugees can obscure internal differentiations in their economic capacities, and universal celebration of refugees’ self-reliance can even undermine refugee protection and welfare. While we should certainly acknowledge and respect refugees’ capabilities and resourcefulness in the face of adversity, we should not dump all responsibilities on the shoulders of refugees alone.

Given the daunting scale of refugees globally, it is undeniable that we need to pioneer new ways to support and enable their socio-economic independence in the long-term. However, making refugee self-reliance a reality necessitates a strong commitment and investment from not only refugee but host governments, the donor community, development agencies, UNHCR, and other relief organizations.

Learn more about The Myth of Self-Reliance: Economic Lives Inside a Liberian Refugee Camp here and read the Introduction for free online.

60% off Gender Studies Titles

As we enter a New Year full of political and economic uncertainty, opportunities in education, and the integrity of evidence-based opinion and decision-making are under attack globally from a populist but neo-liberal philosophy seeking to advance, with depressing success to date, the cause of individualism over the social fabric.

While there will continue to be questions over the character, competence and temperament of many of the world’s political leaders over the coming years, Berghahn will continue to champion the values of accessible scholarly learning, and the spirit of protest, reform, equality and tolerance.

To that end, and with the Women’s March on Washington in mind, we are delighted to offer, in the form of a New Year tonic, a 60% discount off all Gender Studies titles, purchased via our website over the next 7 days. At checkout, simply enter the code NYGEN17.

The books featured below form just a small selection from our complete list of Gender Studies titles. For a full list, please visit our website.

Berghahn Journals: New Issues Published in August

World Refugee Day

The United Nations’ (UN) World Refugee Day is observed on June 20 each year. This event draws public’s attention to the millions of refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide who have been forced to flee their homes due to war, conflict and persecution.

“Refugees are people like anyone else, like you and me. They led ordinary lives before becoming displaced, and their biggest dream is to be able to live normally again. On this World Refugee Day, let us recall our common humanity, celebrate tolerance and diversity and open our hearts to refugees everywhere.” – Ban Ki-moon

Enduring Uncertainty: Deportation, Punishment and Everyday Life

by Ines Hasselberg, University of Oxford

On the 14th of April of 2010, I was approached by J. who had come across my doctoral research webpage when she was desperately searching the net in an attempt to find a way to keep her husband in the UK. My doctoral research was centred on deportation from the UK. What effect do British policies of deportation have on those facing deportation and their families? What strategies are devised to cope with and react to deportation? In what ways does deportability influence one’s sense of justice, security and self, and how does that translate into everyday life? Those were the questions I wanted to, and did, discuss.

Continue reading “Enduring Uncertainty: Deportation, Punishment and Everyday Life”