Alex Tomić discusses her new book, The Legacy of Serbia’s Great War: Politics and Remembrance, which examines the centenary events memorializing the First World War with the retreat at its core and provides a persuasive account of the ways in which the remembrance of Serbian history has been manipulated for political purposes.

I started researching the remembrance of the First World War in Serbia in the run up to the centenary, just over ten years ago. Apart from reading, classifying and analysing, I also needed to visit some of the sites of remembrance, attend ceremonies, museum openings, concerts… whatever I was able to manage while working full-time in the Hague. My husband (was) volunteered as a travelling companion so for the next few years our holidays were spent visiting First World War monuments, usually located at military cemeteries. Apart from places in Serbia and Greece, we also visited memorial sites in France, Belgium, Slovenia, Italy and the Netherlands (although the Netherlands was neutral, there is a twist in Chapter 8 …). Some trips stand out.

In April 2015, we visited Valjevo, a town which was about to commemorate the centenary of the great typhus epidemic when most of Valjevo was made into a giant hospital with multiple buildings housing typhus patients being looked after by different medical missions’ staff. Although I had previously read that the exhibition on Valjevo in 1915 would be opening around this time at the town museum, it was more or less by chance that we actually arrived as the grand opening was about to start. This turned out to be a much bigger deal than we could have imagined. Ambassadors, ministers, academics and dignitaries filled the museum fast. The speeches were held on the plateau in front, the string quartet was also outside. It was a commemorative event in action and I could not have found a better example of it. I also met and spoke with visitors, curators, historians and eavesdropped on what people were saying. It may seem strange to everyone else, but for a researcher this was a perfect day.

We travelled to Corfu in April 2017, having deliberately avoided the centenary events of the previous year which were extensively covered by the Serbian media. A lot of my research focused on the remembrance of the Serbian Army Retreat across Montenegro and Albania of 1915 and the Serbian troops recovery in Corfu in 1916. Despite its importance, the Retreat is not specifically physically memorialised. It is widely considered that the memorial on the island of Vido in Corfu is in fact the closest that the Retreat has as a monument. We spent several days visiting all the sites in Corfu that had any relation to the Serbs, former hospitals, landing sites, existing or former cemeteries. It was Easter week and although it was not yet season for visiting Vido – a small island off Corfu where the Serbian memorial is located – the Serbian House curator told us about the exceptional organised trip on Good Friday. This is how we found ourselves participating in the commemoration that I described in the book. My husband recorded the event and I subsequently transcribed the speeches and translated them into English. I made notes of what the visitors were saying and their demeanour. They were tourists and yet they were so much more. We had found ourselves among pilgrims. But what were we? I was trying to observe but I also participated, feeling moved by what was said and then immediately analysing which word or expression had provoked the emotion and why. As they say, it was all very meta. It also made me wonder whether I had become one of those “infected historians”, as Dutch historian Eelco Runia called those who were too enthusiastic about commemorations (if I was, I think I am fairly immune now).

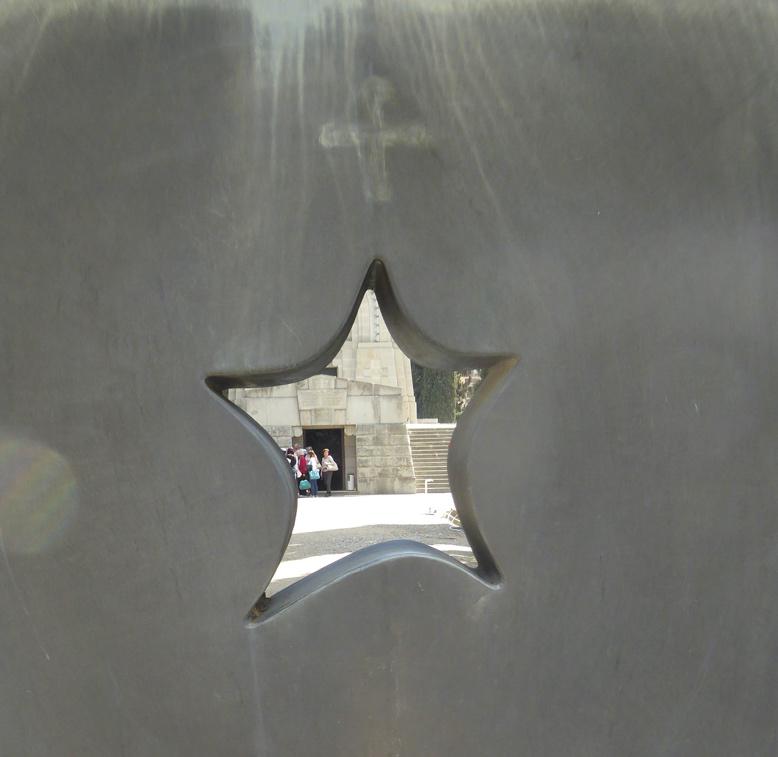

The Serbian Military Cemetery (Zejtinlik) in Thessaloniki was another compelling context to observe remembrance in action. Among the other military cemeteries next door, the Serbian cemetery was an exception as its guard and guide, the legendary Uncle Djordje had actually lived on site since 1961 when his father died, who, in turn, had taken over the duties from his father in 1928. Uncle Djordje, who died in the summer of 2023, was a remarkable host, as the visitors always had the history and poetry recited to them and were then treated to some slivovitz (also in the morning). The crypt with the ossuary boxes was like no other: visitor mementos had piled up for years and the scene appeared both impressive and incongruous. There was so much to notice and to interpret that probably only about twenty percent went into the book. We also visited the other cemeteries in the same complex, including the monument to the Yugoslav partisans who had perished in Salonika’s Nazi-run camps in the Second World War. At one point I observed the visitors going to the main mausoleum crypt through the star-shaped opening in the (communist-era) monument. Then I noticed that someone had drawn a cross above it. It was a perfect symbol of what past was to the Serbs: ‘work in progress’, as I call it in the book.

One of the last events I attended was the main commemoration of the Armistice on 11 November 2018 at the Belgrade main cemetery. The orchestrated ceremony was so different from what I had witnessed in Corfu and Thessaloniki. This one was all official and predictable with several speeches. Again, I am certain they were far more interesting for me as a researcher than for the crowd – who were there clearly because they had to be: the actors, the choir, the diplomatic corps, the official media, the politicians, the hangers-on, the wreath-bearers and sash-adjusters.

This research project is finished, it is now in the book. Still, over the years, war monuments and military cemeteries have become places we always visit wherever we go, regardless of the war, regardless of the side. It seems the only right thing to do.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Alex Tomić is a linguist and historian. She worked as a translator and interpreter at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia from 1994 until 2003, and served as chief of language services at the International Criminal Court between 2003 and 2020. Alex was awarded a PhD in history in 2021 at the University of Leiden. She currently lectures at different universities on the topics of translation and interpretation in international jurisdictions.

THE LEGACY OF SERBIA’S GREAT WAR

Politics and Remembrance

Alex Tomić

Volume 48, Making Sense of History

January 2024, 352 pages, 27 figs.

ISBN Hb: 978-1-80539-233-0 $145.00/£107.00

eISBN 978-1-80539-234-7 $34.95/£27.95