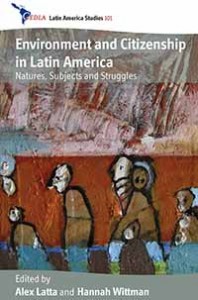

Alex Latta and Hannah Wittman are the editors of Environment and Citizenship in Latin America: Natures, Subjects and Struggles, recently published by Berghahn. The work aims to advance debates on environmental citizenship, while simultaneously and systematically addressing broader theoretical and methodological questions related to the particularities of studying environment and citizenship in Latin America. Here, they discuss the origins of their interest in the topic, where they see the work fitting within the field, and the process of putting the volume together.

Alex Latta and Hannah Wittman are the editors of Environment and Citizenship in Latin America: Natures, Subjects and Struggles, recently published by Berghahn. The work aims to advance debates on environmental citizenship, while simultaneously and systematically addressing broader theoretical and methodological questions related to the particularities of studying environment and citizenship in Latin America. Here, they discuss the origins of their interest in the topic, where they see the work fitting within the field, and the process of putting the volume together.

___________________________

1. What drew you to the study of environmental citizenship?

We were both conducting extensive field research in different parts of Latin America (Wittman mainly in Guatemala and Brazil, Latta in Chile) during the early 2000s, when the field of citizenship studies was really picking up. At the same time, researchers working within a long tradition of “green” social theory started talking about “environmental citizens” and probing questions about what it means to think about ecological questions through the lens of citizenship. In the field we couldn’t help observing the way that struggles over environmental issues were closely bound up with debates over questions of recognition, inclusion, rights and inequality. The connection between environment and citizenship was plain to see in communities’ defense of their land rights, activists’ discourses around biodiversity or pollution, corporate agendas to tap natural wealth and government’s efforts to order and regulate different kinds of human-nature relationships. But as we observed this connection in practice, we were dissatisfied with debates about environmental citizenship amongst scholars from the Global North, which didn’t seem to offer the tools we needed to make sense of what was going on in Latin America. Before we even met we had independently decided to work at conceptual innovation to remedy this shortcoming

2. How did your perceptions of environment and citizenship change from the time you started work on this volume to the time you completed it?

Working on this volume was a good reality check for us. As a scholar it is easy to get wrapped up in one’s own self-referential bubble of theories, case studies and the like. Hearing what other scholars made of this connection between environment and citizenship had two kinds of outcomes. On the one hand, it confirmed our conviction that this is a fruitful intellectual space for thinking about a series of related ecological, social and political questions. There are all kinds of research avenues still to be explored. On the other hand, working with our collaborators during this project also reminded us that the terminology of citizenship, even as an analytical concept, is not innocent nor is there consensus about definitions and meanings. A number of the scholars who participated in the original workshop, including a couple whose pieces found their way into the book, were critical about the way the notion of citizenship potentially imposes a Western political ontology. They also pushed us with respect to the limits of citizenship as an analytical category (compared, for instance, to environmental justice). Even more importantly, these collaborators have demonstrated in their chapters how the discourses and practices of environmental citizenship can and have been mobilized by state and other actors as tools to re-enforce the subordination of politically marginal subjects such as indigenous peoples.

3. Do you think there are aspects of this work that will be controversial to other scholars working in the field?

To the extent that the volume manages to complicate the terms of debate it is definitely our hope that other scholars in the field will feel the need to respond. There is a reason why the book is not titled “Environmental Citizenship in Latin America”. This collection is aimed to decentre the field of study, unsettling the easy union of these terms and putting in their place a more open-ended research agenda around the intersection of environment and citizenship. Obviously, the collection is also meant to stir the pot by reminding scholars that the Global South can’t be ignored as we seek to develop new paradigms of thought around environmental questions.

4. To what extent do you think the book will contribute to debates amongst academics and activists within the Latin American Region?

The fact that the book is in English is a partial barrier to uptake amongst Spanish or Portuguese speaking audiences, though there is an increasing amount of collaboration and cross-fertilization between work conducted in the three different languages, regardless of where it is written and published. Indeed, six of our own contributors are from the region. Moreover, we’ve had excitement about the collection expressed by other Latin American colleagues in research networks to which we belong. There seems to be a hunger amongst scholars and activists in the region for more exploration of the kinds of themes the book’s contributors grapple with. At the same time, in the context of this and other projects we constantly feel that more needs to be done to join up academic debate across the North-South divide, and also to reach out more effectively from the academic sphere into activist circles.

5. Putting together an edited volume is a lot of work. Was it worth it?

The opportunity to collaborate on a volume like this, both in terms of our work together as editors and with respect to the larger network of scholars involved in the project, brings significant rewards. We were lucky to have a really dedicated group of contributors, who worked diligently through numerous rounds of revision. In general there is a lot of good feeling around the collaboration that went into this project, and I think we are all pleased with the outcome.

___________________________

Alex Latta is an Associate Professor in the Department of Global Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University and in the Balsillie School of International Affairs.

Hannah Wittman is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and Associate Member of the Latin American Studies Program at Simon Fraser University.

What drew you to the study of Alexander von Humboldt?

What drew you to the study of Alexander von Humboldt?