Gemma Blackshaw, along with Sabine Wieber, is one of the editors of Journeys into Madness: Mapping Mental Illness in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In her own contribution to the volume, she discusses the work and life of Viennese author and poet and Peter Altenberg. Here, she answers questions about her research and herself.

Gemma Blackshaw, along with Sabine Wieber, is one of the editors of Journeys into Madness: Mapping Mental Illness in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In her own contribution to the volume, she discusses the work and life of Viennese author and poet and Peter Altenberg. Here, she answers questions about her research and herself.

1. What drew you to Peter Altenberg as a topic?

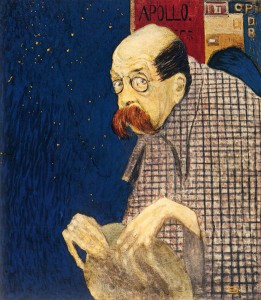

A caricature of Altenberg was chosen as the poster image for the Madness & Modernity exhibition I curated with Leslie Topp and Sabine Wieber, which looked at the relationship between mental illness and the visual arts in Vienna circa 1900 (Wellcome Collection, London and Wien Museum, Vienna, 2009-10). It was a last-minute addition to the exhibition, gratefully received from the Neue Galerie Museum for Austrian and German Art in New York, and I had little time to research its history. I touched upon Altenberg’s own experience of what was termed ‘nervous disorder’ in the accompanying catalogue in an essay on the artist Oskar Kokoschka, who painted Altenberg’s portrait in 1909, and made a mental note to follow up what seemed to me to be an intriguing set of questions: was Altenberg as ‘mad’ as he appeared in the caricature; did an answer to that question even matter; what were the circumstances of his being institutionalised; what was the value and the differences in being represented, and representing yourself, as ‘mad’? These questions formed the starting point of a long research journey which became so compelling a trail that I produced not only this essay but also a documentary film collaboration with artist and filmmaker David Bickerstaff titled Altenberg: The Little Pocket Mirror.

2. How did your perceptions of Altenberg change from the time you started your research to the time you completed your essay?

The research towards my essay involved a great deal of archival work. Altenberg was a prolific letter-writer, and I was able to re-construct his journey in and out of Sanatorium Steinhof through the postcards, letters and inscribed photographs he sent to friends and family; fragile papers that are scattered throughout archives in cities as far-flung as Vienna, New York and Jerusalem. The correspondence revealed unforeseen complexities in Altenberg’s character; I realised that he was both naive and knowing, controlled and controlling. Such complexities informed the approach I took in the essay to Altenberg’s madness as a lived reality and an authorial persona; a debilitating personal illness and a regenerative creative resource; an ‘authentic’ experience and an ‘inauthentic’ representation.

3. Do you think there are aspects of this work that will be controversial to other scholars working in the field?

Altenberg is one of the most controversial figures in the field of Modern Austrian Studies. Most of the debate focuses on his sexuality, and in particular his relationships with girls under the legal age of consent in Austria at that time, which was 14-years-old. The ethical issues raised by his life and work are crucial to acknowledge, but I try to move beyond them to consider, above all, questions of context: why was there such an interest in child sexuality in Vienna circa 1900; how did the ‘child-woman’ emerge as a new artistic and literary trope; and how was the identification of male artists and writers with young women a critique of masculinity? These questions were beyond the scope of my essay for the book, but in focusing on the construction of Altenberg’s identity as the ‘mad’ writer, I challenged the tendency to reduce his life and work to a discussion of his admittedly highly problematic sexuality. Equally, in tying Altenberg’s ‘madness’ to the psychiatric culture of Steinhof, the café culture of Vienna, and the spa-town culture of Semmering, I pointed to the importance of context to the determining of what I consider to be historically-specific and culturally-differentiated relationships between madness and creativity.

4. What’s a talent or hobby you have that your colleagues would be surprised to learn about?

I’m a scrapbooker. Specifically, I cut and paste photographs of interiors – from furniture details to room-scapes – into large notebooks for inspiration when moving house or re-decorating. It explains my fascination with Altenberg’s own and far more interesting scrapbook practice and, connected to this, the decoration of his hotel room walls with photographs, postcards and paper-clippings; an activity he described as nest-feathering.

5. If you weren’t an art historian what would you have done instead?

In my work, I’ve been fortunate enough to dip a toe into all the jobs I would have done instead: novel-writing; book-collecting; film-making; documentary-presenting; exhibition-curating; art-dealing; interior-designing…