It’s odd to see the result of years of work contained within a small object, whether it is a book, a DVD, or a phone on which films are streaming. Stories Make the World contains, in a sense, ideas I care about, a variety of subjects that interest me, and many of the films I’ve worked on.

It was odd as well to see a room enclose people from almost every aspect of my life. That happened at the party celebrating the launch of Stories Make the World. If my life were a book, many of its chapters appeared in my living room one Sunday afternoon. Convening beneath balloons were my brother, a cousin, and their wives, my wife, our son and his girlfriend, friends who live on my block, friends whose children grew up with my children, other friends I hadn’t seen in years, and colleagues I have worked with over the years.

That gathering of people I’ve known over a long span of time in disparate situations offered a sense of my life’s unity. But it was an illusion: a snapshot at a moment in time belies the experience of living. As Kierkegaard wrote in his journals, “Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.” Living forwards, it can be impossible to tell what direction one will take and whether pleasure or distress, success or failure will result. That applies to documentary films, almost every one of which is a high-risk project. It applies, of course, to a book from conception to publication and beyond. And it’s true for everyone’s life. The present moment is pregnant with the future. The outcomes and their connection with what came before become evident only in retrospect.

Looking around the room, I saw the youngest member of my family, two-year-old Nina, resting in her mother’s arms. I wondered, who will she be? What will the world be like when she is a woman? Across the room from Nina and her mother Katie stood Douglas Sharon, an explorer in Perú who, when we first met in our early twenties, was discovering ancient cities that Andean jungle had covered. His friendship with the shaman Eduardo Calderón inspired a career change: Douglas became an anthropologist.

I caught the eye of Claire Schoen. When we met, I was a playwright working with a comedic theater company and she was a documentary filmmaker. Living with her, I entered the community of independent media professionals in the Bay Area. Members of that community listened as I read passages from Stories Make the World: Judy Irving who, when I met her, was making Dark Circle, a mind-opening film about the nuclear age, with Chris Beaver and Ruth Landy; Ruth, who produced international media for the World Health Organization after Dark Circle premiered; Justine Shapiro, who apprenticed with Judy and Chris, then went on to make Promises, the Emmy-winning, Academy Award-nominated film about Israeli and Palestinian children; Gina Leibrecht, who has edited two films I’ve worked on: A Land Between Rivers and Wilder than Wild; and the director of those films, Kevin White, who arrived late, bringing a bottle of bubbly.

At that moment in time in that place, which seemed to encompass innumerable stories in my life and theirs, I released into the world a small object that I hope will be fruitful.

See an earlier blog post from Stephen Most here, and learn more about the book Stories Make the World: Reflections on Storytelling and the Art of the Documentary here. To stream and download films in Stories Make the World, go to www.videoproject.com/Stories.

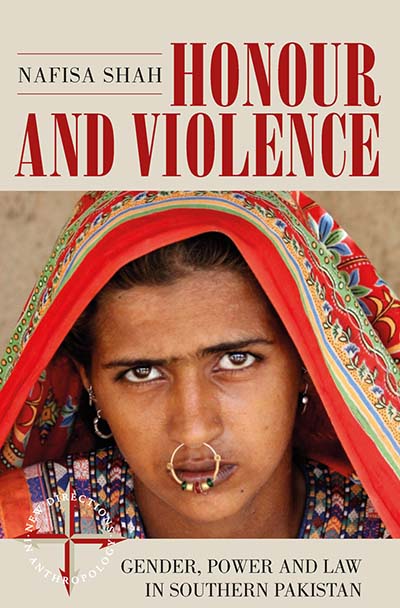

The following is an interview with Nafisa Shah about hew new book Honour and Violence: Gender, Power and Law in Southern Pakistan.

The following is an interview with Nafisa Shah about hew new book Honour and Violence: Gender, Power and Law in Southern Pakistan.

From Virtue to Vice: Negotiating Anorexia

From Virtue to Vice: Negotiating Anorexia