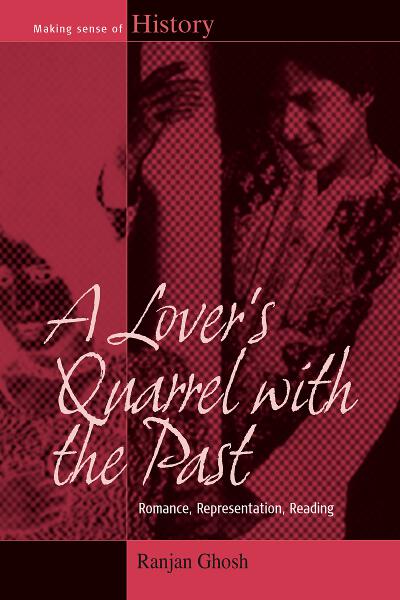

Note: Berghahn recently published Ranjan Ghosh’s A Lover’s Quarrel with the Past: Romance, Representation, Reading, an exploration of the relationship between history and theory. Here the author talks about the origins for the section on dust that appears in the book.

Note: Berghahn recently published Ranjan Ghosh’s A Lover’s Quarrel with the Past: Romance, Representation, Reading, an exploration of the relationship between history and theory. Here the author talks about the origins for the section on dust that appears in the book.

__________________________________

Dust

I suffer from a dust allergy. If I’m really careful, it wouldn’t affect my life in any significant way. For what, after all, are allergies? A few crustaceans managing to live out their lifespan because a gourmet friend of mine suffers from a seafood allergy. Compared to that exchequer, my allergy has almost no exchange value. I can joke about it, although, only in the way a bald stand-up comedian can joke about his hair or lack thereof. For the truth is this: my relationship with dust has affected the way I have done history.

My mother, whose mythical bedtime stories first introduced me to history as a child, was a historian. Her specialisation was numismatics but she eventually gave up teaching history to take over curatorship of the university museum. She was also diagnosed with asthma — a disease for which dust is an enemy — and she suffered especially during the dusty Indian winter months. I subsequently grew up with a psychosomatic hatred for dust: a maid cleaned our house twice a day and I became the subject of much teenage laughter in school, holding, as I did, a hankie to my nose at all times.

Now, why do I say all this? My book, A Lover’s Quarrel with the Past: Romance, Representation, Reading, has a section on dust. When I first read Carolyn Steedman’s fine book, Dust: The Archive and Cultural History (it was published exactly a year after my mother’s death), I was overcome by several strong emotions. Primary among them was a sense of despair. Like my mother who would wheeze at the mention of a furry animal or sandstorm, I read Steedman’s book literally out of breath. My sense of despair came from the realisation that I would never be able to work in an archive — that I would never have a career in dust.

My Lover’s Quarrel is, in that sense, also a quarrel with dust, my private trope for history, the past and the future, beyond the biblical from where we come to where we go.

There is a living, buoyant ligature between a historian and the archival milieux where one encounters the recorded past as much as a ‘history of loss’, where the dust rests as no mere squalid accretions but animated particles that can waft into the historian with differential vibrations….Dust speaks; dust makes us aware of a past that is absent and present at the same time, a temptation to the historian’s reconstructionist desires and a reminder of his or her affiliation to grounded evidence. In a kind of sensory encounter with the past, dust, as a materiality, awaits mediation, conjuring up the ‘presence’ of the past. (102)

My book combines South Asian history with the continental philosophies of history. But my accusative finger is at dust and my physiological condition, which has prevented me from being a ‘proper’ historian. I’ve written on textbooks and pamphlets, and their unique semantics of a propagandist historicising, but I’ve always had to take the help of someone, a kind acquaintance at the library, often my wife or father, to first wipe the dust away from their pages before I could examine them.

That has also become my shorthand for doing history: wiping the dust. In that there is much romance and representation, and of course, always, always, a new reading.

__________________________________

Ranjan Ghosh teaches in the Department of English at the University of North Bengal, India. Featuring lectures and a panel discussion on the book,

Lover’s Quarrel will be launched on September 21 at the University of North Bengal.

Soon after the Israeli forces occupied Sinai in 1967 the peninsula was inundated with many kinds of tourists and journalists. I avidly listened to their glowing accounts of the Bedouin of Sinai. Yet for several years I hesitated to visit Sinai. I wavered between fear and hope that I would be tempted to study the Bedouin, and again experience the intellectual and emotional tumult of my earlier study of the Negev Bedouin.

Soon after the Israeli forces occupied Sinai in 1967 the peninsula was inundated with many kinds of tourists and journalists. I avidly listened to their glowing accounts of the Bedouin of Sinai. Yet for several years I hesitated to visit Sinai. I wavered between fear and hope that I would be tempted to study the Bedouin, and again experience the intellectual and emotional tumult of my earlier study of the Negev Bedouin. Berghahn has just released Two Sides of One River: Nationalism and Ethnography in Galicia and Portugal, an English translation by Martin Earl of the original Portuguese volume by António Medeiros. This book explores the historical intersections between nationalism and the emergence of ethnographic traditions in Portugal and Galicia, and plays this history against the author’s own ethnographic research in both places at the turn of the 20th century.

Berghahn has just released Two Sides of One River: Nationalism and Ethnography in Galicia and Portugal, an English translation by Martin Earl of the original Portuguese volume by António Medeiros. This book explores the historical intersections between nationalism and the emergence of ethnographic traditions in Portugal and Galicia, and plays this history against the author’s own ethnographic research in both places at the turn of the 20th century. the 1990s under the stewardship of the city’s first directly elected mayor, former communist Antonio Bassolino. Through the study of two major piazzas and a squatted centro sociale (social centre), the book explores the pivotal role of public space in the administration’s efforts to reorder and redefine a city that had hitherto been commonly regarded as an urban outcast. It thus sets out to investigate how changes to the built environment were, on the one hand, produced and publicly endorsed and, on the other, experienced and contested by different groups of people. Understanding public space means grappling with the messy and perhaps ugly pluralism that constitutes urban life, rather than unwittingly confirming normative and institutional ideals about a ‘good’ (and, especially in the case of Naples, ‘well-behaved’) city.

the 1990s under the stewardship of the city’s first directly elected mayor, former communist Antonio Bassolino. Through the study of two major piazzas and a squatted centro sociale (social centre), the book explores the pivotal role of public space in the administration’s efforts to reorder and redefine a city that had hitherto been commonly regarded as an urban outcast. It thus sets out to investigate how changes to the built environment were, on the one hand, produced and publicly endorsed and, on the other, experienced and contested by different groups of people. Understanding public space means grappling with the messy and perhaps ugly pluralism that constitutes urban life, rather than unwittingly confirming normative and institutional ideals about a ‘good’ (and, especially in the case of Naples, ‘well-behaved’) city. Note: Berghahn recently published Ranjan Ghosh’s

Note: Berghahn recently published Ranjan Ghosh’s