Heritage-Making, Bagamoyo, and the East African Caravan Trade

BY JAN LINDSTRÖM

Continue reading “Muted Memories”

BY JAN LINDSTRÖM

Continue reading “Muted Memories”BY ANDREW REINHARD, author of ARCHAEOGAMING: An Introduction to Archaeology in and of Video Games

September 12 marks the 22nd annual National Video Games Day, a day with hazy origins. When I think about time and video games, a few things come to mind: anniversaries of course, release dates, retirement dates. I found myself wondering: what commercial games premiered in September 1997, the first official #VideoGamesDay (which was the first year I could start buying games for myself with discretionary income)? There are some classics, all for Windows/DOS: Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee, Ultima Online, Fallout. There are also some games lost to time: Breath of Fire III, Croc: Legend of the Gobbos, Close Combat: A Bridge Too Far, Panzer General II, Poy Poy, and Total Annihilation.

Continue reading “Portable, Digital Heritage and Memories of Place”

My book Desires for Reality: Radicalism and Revolution in Western European Film was first published in 2016, and Berghahn Books just published a paperback edition.

Since the book concerns militant and radical film and film-making and the events of 1968, I very much wanted it to be out before 2018. My intention was that the book could contribute to the discussions that marked the 50th anniversary of 1968, and indeed it did. The ideal, in thinking about 1968, would not be commemoration and nostalgia but an engagement with the ideas of 1968 and their relevancy and challenge to today – that the collective desire to change our realities still, of course, remains, and film-making can still be considered in this context.

While the book deals with many of the now commonly accepted “classics” of that period, it also attempts to recover some still obscure films. In fact, it’s the existence of this divide – between the canonical and the Curate’s Eggs – that was a point of investigation. And, after the book was first published, the reactions to the November 2018 deaths of two film directors who featured heavily in it – Nic Roeg at 90 and Bernardo Bertolucci at 77 – further illustrated this sense of a divide. Their ’68 films are Performance (which Roeg co-directed by Donald Cammell) and Partner respectively. Continue reading “Reverse Angle: Fifty Years of the Cinema of 1968”

For those interested in the economy, by which I mean business, government economic policies, people’s work and their material well-being, the past few decades have been interesting times. Economy, Crime and Wrong in a Neoliberal Era is the result of trying to make sense of things. Continue reading “Economy, Crime and Wrong in a Neoliberal Era”

By Dolores L. Augustine, author of Taking on Technocracy: Nuclear Power in Germany, 1945 to the Present.

By Dolores L. Augustine, author of Taking on Technocracy: Nuclear Power in Germany, 1945 to the Present.

Energy policy has recently gained a good deal of public attention. “Germany, as far as I’m concerned, is captive to Russia because it’s getting so much of its energy from Russia,” President Trump argued at the NATO summit on July 11, 2018. Let’s set aside the faulty data underlying this argument and Trump’s own friendly policies towards Russia and turn instead to a more fundamental question: How wise have German energy policies been? Germany has taken a very different path from that of the United States, deciding in 2011 to abandon nuclear power by 2022. However, Germany has also committed itself to reducing use of fossil fuels. Has this placed German policymakers in a bind? Would life have been easier for Germany if it had not turned away from nuclear power? To understand the present-day situation, we must first look at its historical roots.

Why did Germany turn away from nuclear power? Continue reading “Has Germany’s turn away from nuclear power been a mistake?”

by Anna Saunders, author of Memorializing the GDR: Monuments and Memory after 1989.

by Anna Saunders, author of Memorializing the GDR: Monuments and Memory after 1989. Recent years have witnessed fierce debates about the existence of controversial monuments around the world – most notably Confederate monuments and memorials, but also numerous structures built in honour of wealthy benefactors with murky pasts. The outcomes of such debacles have been varied. In the UK, Oriel College, Oxford, has recently stated its intention to keep its statue of Cecil Rhodes, whereas Bristol’s Colston Hall – named after the slave trader Edward Colston – will be renamed when it reopens in 2020. It seems that the future of monuments may be limited. Yet this depends on our understanding of the role of such structures. In this context, it is worth casting an eye towards Germany, a country whose twentieth century history has prompted the destruction – and construction – of monuments and memorials at a pace rivalled by few others. Continue reading “Why monuments still have a future”

by Robert Orttung

by Robert OrttungMore than four million people live in the Arctic, but so far few scholars have addressed urban conditions there. In fact, most people living in the Arctic reside in cities. Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities: Resource Politics, Migration, and Climate Change is one of the first to try to examine how sustainable these cities are.

The edited volume Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities grew out of a multi-disciplinary and multi-national team of scholars interested in the Arctic. The idea to focus on cities came from one of the book’s contributors, Nikolay Shiklomanov, during a meeting of faculty with an interest in the Arctic at George Washington University. Participants represented both natural scientists who study permafrost and climate change, and social scientists interested in migration and energy development. Cities proved to be the meeting ground where all of our interests converged. As resource extraction continues in the Arctic, more workers are moving to the region and building more infrastructure there. However, the extraction and subsequent combustion of fossil fuels leads to warming in many parts of the Arctic, typically at a rate much faster than on other parts of the planet.

The focus of this book is on Russian cities in the Arctic because Russia has gone the farthest of the Arctic countries in developing urban space in the far north. Stalin built large cities in the region as did subsequent Soviet leaders in an effort to develop the rich resources found there.

The book addresses the question of how humans can live in the Arctic while having minimal impact on the environment. There are no easy answers, so the various chapters consider the history of Arctic development in the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia, policy-making processes for the Arctic in Moscow, the administration of specific Arctic cities, the nature of the workers who make their living in the Arctic, the prospects for land and sea transportation in the region, and what we know about the future climate.

This book is the first of several that we hope to publish in an on-going research project. Currently, Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities serves as a foundation for developing an Arctic Urban Sustainability Index. This index will examine five types of variables – economic, social, environmental, governance and planning. The Index is in its early stages and we are reporting progress over time at our project website. The most recent publications include two reports in the 2017 Arctic Yearbook. The project has the support of the National Science Foundation Partnerships for International Research and Education.

We hope that readers from a wide variety of disciplines and perspectives will find the book useful in starting to think more serious about cities in the Arctic. Ultimately, we hope that this research program will lead to useful advice for mayors and other Arctic policy makers as they try to improve lives for the citizens of Arctic cities.

Robert W. Orttung is the research director for the George Washington University Sustainability Collaborative. He is also an associate research professor at GW’s Elliott School of International Affairs. He has written and edited numerous books on Russia and energy politics.

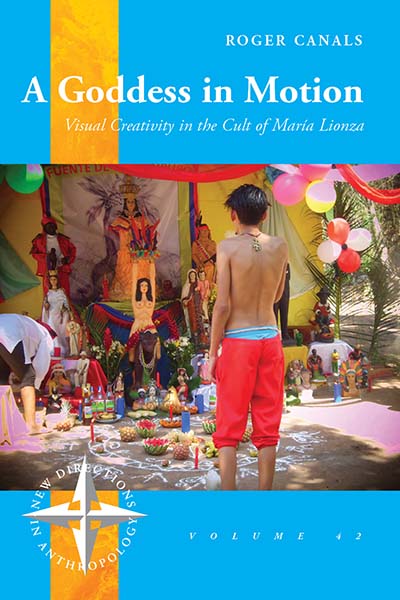

By Roger Canals, lecturer in the department of social anthropology at the University of Barcelona.

By Roger Canals, lecturer in the department of social anthropology at the University of Barcelona.

The book A Goddess in Motion: Visual Creativity in the Cult of María Lionza finds its origins in my vivid interest in Afro-Latin American religions, art and visual anthropology. I understand the latter in a broad sense, that is, as an anthropology of images, as an exploration on the act of seeing and being seen, as a visual ethnography and, lastly, as an attempt to write and publish the outcomes of our research, including visual material.

The main goal of A Goddess in Motion: Visual Creativity in the Cult of María Lionza is to explore how this goddess is represented and what people do with –and through– her images in contemporary Venezuelan society and abroad. For those who do not know this amazing figure, let me tell you that María Lionza is a fascinating goddess, still highly unexplored by academia: symbol of the Venezuelan identity, she is represented as Indian, White, Mestiza and as a Black woman, sometimes benevolent and sometimes evil, at once represented with a high sexual component and at once depicted as a mature woman close to the Virgin Mary. The images of María Lionza may be found in many different locations, where they play a variety of roles: on religious altars, in museums and galleries, on television, on the Internet or on the walls of the streets of Venezuelan cities, to mention just a few. Moreover, María Lionza can “descend” into the mediums’ bodies or “appear” in dreams, visions and apparitions.

The challenge of this book is to think of all these images (material, corporeal and mental) as a whole, that is, as a sort of dynamic and open network in which practices, discourses and visual representations mingle.

How we think about and what we think of as money is constantly changing. And in many cases, those changes are driven in locales that are not necessarily centers of global capital. Consider for the instance of the relatively recent introduction of “mobile money”. In 2007, the Kenyan mobile network operator, Safaricom, launched a mobile payment service named M-Pesa. The service enabled people with no bank accounts (and no access to bank branches) to send and receive money via their mobile phone. By 2011, the service had enlisted 17 million subscribers; by 2014, it was estimated to have double the number of people using formal financial services in Kenya (from 30 percent in 2006 to 65 percent in 2014); in 2018, Google Play started accepting payments via M-Pesa for apps bought online in Kenya. M-Pesa is routinely cast as a technological innovation from the postcolonial South that is ushering in a new wave of financial exclusion for the so-called “unbanked.” Over the last decade, leading international organizations such as The World Bank, government agencies such as USAID, industry trade bodies such as GSMA, and private philanthropic foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mastercard Foundation have embraced (and are heavily investing in) mobile money and other electronic and digital financial instruments for the purpose of financial inclusion. The proliferation of mobile money in the global South and its embrace as a quick-fix to financial inclusion raises a number of questions of interest to scholars and policymakers of money and development: How, if at all, do new forms of money impact people’s everyday financial lives? How do these technologies intersect with other financial repertoires as well as other socio-cultural institutions? How do these technologies of financial inclusion shape the global politics and geographies of difference and inequality?

Continue reading “Changes in the Uses and Meanings of Money”