This post is the transcript of an electronic interview between D. S. Farrer and Jean-Marc De Grave. Farrer is the special issue editor for Social Analysis Volume 58, Issue 1, and De Grave is the author of the article Javanese Kanuragan Ritual initiation: A Means to Socialize by Acquiring Invulnerability, Authority, and Spiritual Improvement appearing in that issue. Below, De Grave answers a series of questions related to his article in Social Analysis.

This post is the transcript of an electronic interview between D. S. Farrer and Jean-Marc De Grave. Farrer is the special issue editor for Social Analysis Volume 58, Issue 1, and De Grave is the author of the article Javanese Kanuragan Ritual initiation: A Means to Socialize by Acquiring Invulnerability, Authority, and Spiritual Improvement appearing in that issue. Below, De Grave answers a series of questions related to his article in Social Analysis.

This is the second in a series of interviews with contributors to this volume. Read D. S. Farrer’s interview here.

What drew you to the study of War Magic & Warrior Religion?

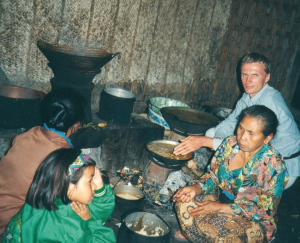

Studying Javanese rituals, I noticed that all anthropologists – including Clifford Geertz – never described the Javanese ritual martial initiation. It was all the more incomprehensible that historians – M.C. Ricklefs, notably – have well shown how deep warrior Javanese hegemony was in Southeast Asia; this is even true at the time of Geertz’s fieldwork during the Suhartoist regime. This example shows once more that people living in protected social contexts mainly used to see and study ‘peaceful’ activities. I understand that more or less secret activities are harder to study, but it is not a reason to ignore them, especially when everyone knows they exist.

Did any perceptions on the subject change from the time you started your research/compiled the contributions to the time you completed the volume?

It might be that initiation practices are of a very great importance to give confidence to the younger generations. In this aim, the difficulties of life – and not only the hardness of studying through intellectual activity – should not be obscured from practices in everyday life: participating in collective actions, experimenting in concrete activities, using one’s body and not letting it becoming a stranger to ourselves.

What aspect of researching and writing the chapter did you find most challenging? Most rewarding?

I could not give all my fieldwork descriptions in the chapter (you can find them in de Grave 2001 if you can read French), but comparative case studies with modern Javanese initiation schools show that nothing can be done without magic, and if one ignores this, one creates a kind of a sad world. At any given moment, the magic will call us back or it will take its revenge!

Concerning the editing work, it has been such a great pleasure to work with D.S. Farrer, thanks to his dynamic, motivating and innovative approach, and – at the end of the process – with Shawn Kendrick (of Social Analysis), the best copyeditor I have ever worked with.

To what extent do you think the book will contribute to debates among current and future academics within the field?

The book clearly shows that the question of social peace is not restricted to the military and police domains. The monopoly of war and violence is a political one such as it has been shown by Pierre Clastres in the 1960’s. Our book pursues this statement (which contributed to erect political anthropology in France). But if we consider magic and religion as a part of war, and vice versa, the secular way of considering things is highly challenged as it presents itself to be universal when in the quantitative facts it is not that significant.

Do you think there are aspects of this work that will be controversial to other scholars working in the field?

It might be that the contributions are more orientated towards a phenomenological experience tied to the ethnography itself rather than starting from the general social organisation.

If you weren’t an anthropologist, historian, what would you have done instead?

Primary school teacher.

What’s a talent or hobby you have that your colleagues would be surprised to learn about?

Gardening.

What inspired your love of the subject of War Magic? When?

I think it was basically my teenage crisis period when I didn’t and couldn’t find any adapted initiation to enter adulthood. I finally found it during my Indonesian and more especially Javanese fieldwork. For me it took time to gain access to a certain kind of adulthood, but it also means that adulthood defined as clear consciousness of where stands violence and what to do to prevent it is not valued in the supposedly protected social contexts, hence we may perceive a general lack of respect to others existence and to the social, physical and natural environment.

What inspired you to research and write?

Researching, writing, and thinking are difficult, rarely valued tasks. These activities require a long process, and research may often be late in the evolution of times especially as regards the ethical dimensions of social facts. The quest for knowledge is inspiring but hard to enact and needs solid motivations.

What is one particular area of interest or question, that hasn’t necessarily been the focus of much attention, which you feel is especially pertinent to your field today and in the future?

What is really education, I mean in everyday practice and not only at school. Besides this, what do we effectively learn at school: social practices, social values, the sense of responsibility/irresponsibility, and so on. That’s what I’m working on now and to my mind it is directly linked to traditional initiation: the separation of the young initiands from the rest of society, to fight and compete with their class and age cohort, to learn ultimate values. The problem is that the ultimate values formally taught at school are so abstract, whereas, in fact, other values are finally taught. In the end, the shift between school context and so-called “working life” is enormous.

References

Clastres, Pierre 1977 Archéologie de la violence. La guerre dans les sociétés primitives, Paris, L’Aube.

De Grave, Jean-Marc 2001 Initiation rituelle et arts martiaux: Trois écoles de kanuragan

javanais, Paris: Archipel/L’Harmattan.

Geertz, Clifford 1960 The Religion of Java, The University of Chicago Press.