In Bodies in Pain: The Emotion and Cinema of Darren Aronofsky, Laine explores the emotionally engaging nature of this prominent director’s work, which includes Requiem for a Dream and Black Swan, Pi and The Fountain. Following, the author explains how she came to write this book, as well as some emotional nuances in the director’s oeuvre.

In 2011 when I was asked by Mark Stanton, then-senior editor at Berghahn Books to write a book about emotion and film aesthetics in the cinema of Darren Aronofsky, my book entitled Feeling Cinema had just been released a month before. At that point I was not planning to start a new book project any time soon, and nor did I have a clue where the next idea for a book would come from, so his proposal almost appeared to me as a gift from the universe. Furthermore, since Aronofsky as a filmmaker was not an obvious choice for me to write about, it was an extra challenge to come up with an aesthetically meaningful starting point, without falling into the trap of cheap auteurism.

My previous book was not so much an account of what cinematic emotions ‘are’, but had rather been a plea for a method that endorsed a mode of thinking through emotions that emerge out of an aesthetic experience. For this reason it seemed appropriate to put my proposed methodology into action while engaging with the affective-aesthetic specificity of Aronofsky’s films.

This resulted in the insight that our affective responses to Aronofsky’s films could be a basis for philosophical reflection regarding knowledge (Pi), addiction (Requiem for a Dream), loss (The Fountain), self-deception (The Wrestler) and bodily materiality (Black Swan). In other words, a precise interpretation of the aesthetic organization of a film may open up important avenues for affective ways of thinking about cinema that in turn may lead to larger philosophical issues (and vice versa).

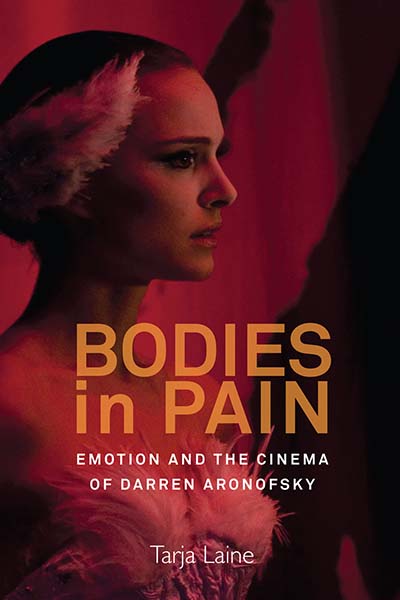

For instance, through its affective-aesthetic specificity, Aronofsky’s Black Swan communicates important insights into the relationship between body and soul, thus anticipating the possibility of reflection on the distinction between ‘having a body’ and ‘being a body’. Losing sight of the material fact of existence that one does not just have a body, but that one is a body, will result in loss of soul, which is what the film embodies in meaning. This is the true tragedy of Nina, the protagonist of the film played by Natalie Portman. In her struggle for perfection, Nina’s place in the world becomes occupied by a disembodied, immaterial hallucination, while she herself falls into a void.

It is this kind of discrepancy between the corporeal and the mental that Aronofsky’s cinema often seems to exploit, epitomized in the troubled relationship between feeling bodies in pain and psychological minds in turmoil.

_____________________________________

Tarja Laine is Assistant Professor of Film Studies at the University of Amsterdam, and Adjunct Professor of Film Studies at the University of Turku, Finland. She is the author of Feeling Cinema: Emotional Dynamics in Film Studies (2011) and Shame and Desire: Emotion, Intersubjectivity, Cinema (2007).