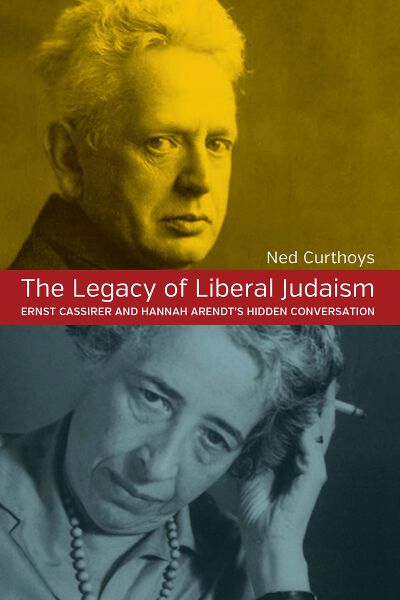

Hannah Arendt was a German-Jewish political theorist; Ernst Cassirer was a German-Jewish philosopher. The ‘liberal Jewish ethics’ of the two come together in Ned Curthoys’ The Legacy of Liberal Judaism: Ernst Cassirer and Hannah Arendt’s Hidden Conversation. The author explains below his fascination of and engagement with the scholars.

_____________________________________

Berghahn Books: What exactly do you mean by the term ‘liberal Judaism’?

Ned Curthoys: Well it’s a diasporic phenomenon, a very interesting response to the twin challenges of secular modernization and inveterate Christian inspired anti-Judaism.

The key tenet is a dynamic and deterritorialised conception of Judaism as beholden to the Prophetic matrix of critical reformism and visionary idealism. There’s an evolving sense that one must be of but not entirely inside the Jewish community, invigorating Jewish thought by maintaining all sorts of ‘thick’ relations and affiliations with the non-Jewish world. Any attempt to essentialise the Jewish religion or people is vigorously opposed by liberal Jews – that way lies xenophobia and stultification. The beauty of Judaism is its capacity to absorb new phenomena.

BB: What brought you to the study of German-Jewish philosophers, specifically Hannah Arendt?

NC: When I was doing my Ph.D. on the contemporary theoretical legacy of classical rhetoric, my friend Dirk Moses, a genocide and Holocaust historian, mentioned Arendt’s work to me and I was immediately intrigued and soon entranced by the boldness and depth of her thinking. I started reading Arendt well before I saw myself as someone who could contribute to Jewish studies or German-Jewish intellectual history. Still, it didn’t take too long to get a sense that she was part of a broader milieu of humanistic German-Jewish intellectuals whose social and institutional marginality enabled a breadth of vision and a personal point of departure that we still cherish.

BB: Did any perceptions on the subject change from the time you started your research to the time you completed the book?

NC: A lot of the thinking for this book materialized in the drafting, for example I didn’t originally envisage Hermann Cohen would need a separate chapter, but there was no other way to dignify the Cassirer/Cohen relationship. But my gut instinct, that if we don’t acknowledge the great tradition of liberal Jewish thought subtending Arendt’s theoretical and political interventions the conversation around her will remain jejune and strangely conventional – that was there from the start.

BB: What aspect of writing this work did you find most challenging? Most rewarding?

NC: Writing a monograph in any field of intellectual history is incredibly difficult, particularly in an area like this one, since Arendt studies and German-Jewish history are highly politicized. Then there’s the problem of trying to forge a new kind of conversation about Arendt’s political and ethical co-ordinates. On the other hand Arendt knew all about the importance of theorizing without banisters, of resisting the temptation to nestle into a canonical narrative.

BB: To what extent do you think the book will contribute to debates among current and future academics within the field? How does it add to the dialogue of German-Jewish philosophy?

NC: I’d like to think that in addition to situating Arendt as a contributor to an always already imaginative and iconoclastic liberal Jewish philosophical tradition, the book will further counter some of the more dismissive conceptions of both Ernst Cassirer and Hermann Cohen as bourgeois, deluded, unrealistic, naïve. I hope their profound contribution to Jewish letters will finally be recognized.

BB: Do you think there are aspects of this work—specifically as it pertains to Arendt—that will be controversial to other scholars working in the field?

NC: If you’ve already decided, largely because of your disciplinary training, that there’s one other philosophical interlocutor that really matters in Arendt studies, and that’s Martin Heidegger, then you might be a touch put out.

BB: Who is one iconic figure featured in one way or another in your field of research, living or dead, for whom you have particular admiration and why?

NC: It’s Cassirer, but he’s far from iconic. He was a brilliant, adventurous, and profoundly humane thinker, and a tireless advocate for Jewish interests in incredibly difficult circumstances.

_______________________________________

Ned Curthoys is a research fellow in English at the Australian National University. With Debjani Ganguly he is co-editor of Edward Said: The Legacy of a Public-Intellectual (Melbourne University Press, 2007).