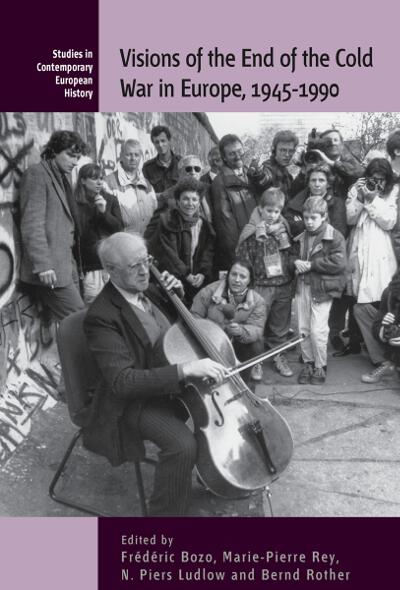

When WWII drew to a close in the late 1940s, the fighting may have stopped, but the tension was just building. This sustained Cold War friction lasted longer than four decades, the whole time of which, the main players had ideas of how it would look when it ended. The editors and contributors of Visions of the End of the Cold War in Europe, 1945-1990, to be published next month, explore these ‘conceived programmes’ and ‘utopian aspirations.’ Below, an excerpt from the Introduction sets the scene, starting at the end, with the fall of the Wall.

___________________________________________

The fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 quickly came to symbolize the end of the Cold War as a whole, including the liberation of Eastern Europe from Soviet rule in 1989, the unification of Germany in 1990 and the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991. Its twentieth anniversary in autumn 2009 was therefore an opportunity to celebrate not just that particular event – however meaningful – but an extraordinary period that in barely two years led from the dismantling of the Iron Curtain to the liquidation of the whole ‘Yalta’ order.

Yet the celebrations were not only a commemorative moment but also a historiographical one, marking the culmination of almost twenty years of ceaseless scholarly production on the end of the Cold War. Innumerable academic events were held on the anniversary itself in order to revisit the period, and a wealth of new works predictably came to enrich an already considerable literature. Furthermore, this clearly is not the end: as historical evidence continues to become accessible as a result of the regular opening of archives after the standard twenty to thirty years, the end of the Cold War is likely to keep historians busy for quite some time to come.

There are numerous explanations for the infatuation that continues to prevail among scholars and the general public with the end of the Cold War. The sheer historical importance of the period ranks high amongst them: the events of the late 1980s and early 1990s – often described as the ‘revolutions of 1989’ – were hugely momentous because they terminated four decades of East-West conflict, of the division of Germany, and of the domination of communism in Eastern Europe, all of which had defined the second half of the twentieth century on the continent. In a sense, the 1989–91 period even marked the definitive end of the ‘short’ twentieth century itself – an era of total conflicts and totalitarian ideologies.

But another reason for the fascination aroused by these events is their unexpected and, indeed, their unpredicted character. To be sure, by the late 1980s the notion that the Cold War would end someday was generally recognized, but usually more as a theoretical point than as a definite prediction – in fact, the longer the Cold War lasted, the more it was perceived as likely to last for an indefinite period of time. In truth, those individuals – whether decision-makers or thinkers – who had effectively foreseen the end of the Cold War as it happened were few and far between. Even less numerous, in particular, were those who had sensed that the process could be both as rapid and as orderly as it turned out to be, a combination that certainly remains to this day the most remarkable characteristic of the events of 1989–91.

And yet the end of the Cold War had been a constant and recurrent theme throughout the whole duration of the Cold War itself. Ever since its inception in the second half of the 1940s, statesmen, diplomats, politicians, academics and others had reflected on ways of ending the East-West conflict and overcoming its undesirable consequences. As the Cold War settled in – most clearly by the late 1960s – the East-West status quo no doubt increasingly came to be seen by most contemporaries as an enduring reality. Yet the situation was, arguably, never considered to be irreversible in the long term: even at times when the established order appeared to have become all but perennial, the need to overcome it and the ways to do so were more or less openly or more or less intensely and passionately discussed.

It is remarkable, therefore, that recent historiography has not more systematically sought to explore and investigate the visions of the end of the Cold War that were articulated and offered before the end of the Cold War took place. This is precisely the subject of this volume. The following collection of essays, then, is not an umpteenth book on the end of the Cold War itself. Rather, it is an attempt at envisaging the entire Cold War through a prism that has arguably not been used systematically by historians or international relations specialists before: the retrospective analysis of the conceptions of the demise of the ‘Yalta’ system that emerged in the course of the four decades of Cold War.

_______________________________________________

Frédéric Bozo is Professor of History and International Relations in the Department of European Studies at the Sorbonne (University of Paris III). His publications include Mitterrand, the End of the Cold War, and German Unification (2009) and Two Strategies for Europe: De Gaulle, the United States and the Atlantic Alliance (2001).

Marie-Pierre Rey is Professor of Russian and Soviet History and Director of the Centre of Slavic Studies at the Sorbonne (University of Paris I). Her publications include Alexandre Ier, le tsar qui vainquit Napoléon (2009) and Europe and the End of the Cold War: A Reappraisal (ed., 2008).

N. Piers Ludlow is a Reader in the Department of International History of the London School of Economics. He recently published The European Community and the Crises of the 1960s: Negotiating the Gaullist Challenge (2006).

Bernd Rother is a Historian at the Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt Foundation in Berlin. He is editor of Willy Brandt: Über Europa hinaus. Dritte Welt und Sozialistische Internationale(2006) and Willy Brandt: Gemeinsame Sicherheit. Internationale Beziehungen und deutsche Frage 1982-1992 (2009).

Series: Volume 11, Contemporary European History