In the past three decades within India, a knowledge of the English language has become more important for economic advantage. All the while, Hindi is essential to those who wish to pursue class mobility. These “mediums” form a divide within the country’s educational system, which come to the forefront in Chaise LaDousa’s Hindi is our Ground, English is our Sky: Education, Language, and Social Class in Contemporary India, published this month. Following are two excerpts from the book, the first from the Foreword by Krishna Kumar, and the second from the Preface.

__________________________________________________

[Chaise LaDousa] has studied India’s vertical language divide in the North Indian city of Varanasi. The study takes us well beyond the shibboleths proffered about India’s linguistic plurality. The key word that enables LaDousa to enter the separate yet interwoven milieus of Varanasi is “medium.” The term is so omnipresent in the Indian urban environment that no one marvels at the versatile service it renders to India’s society and state. It resides securely in the phrase “medium of instruction” that is used across India as a public code to identify two types of schools and the opportunity markets to which they promise access.

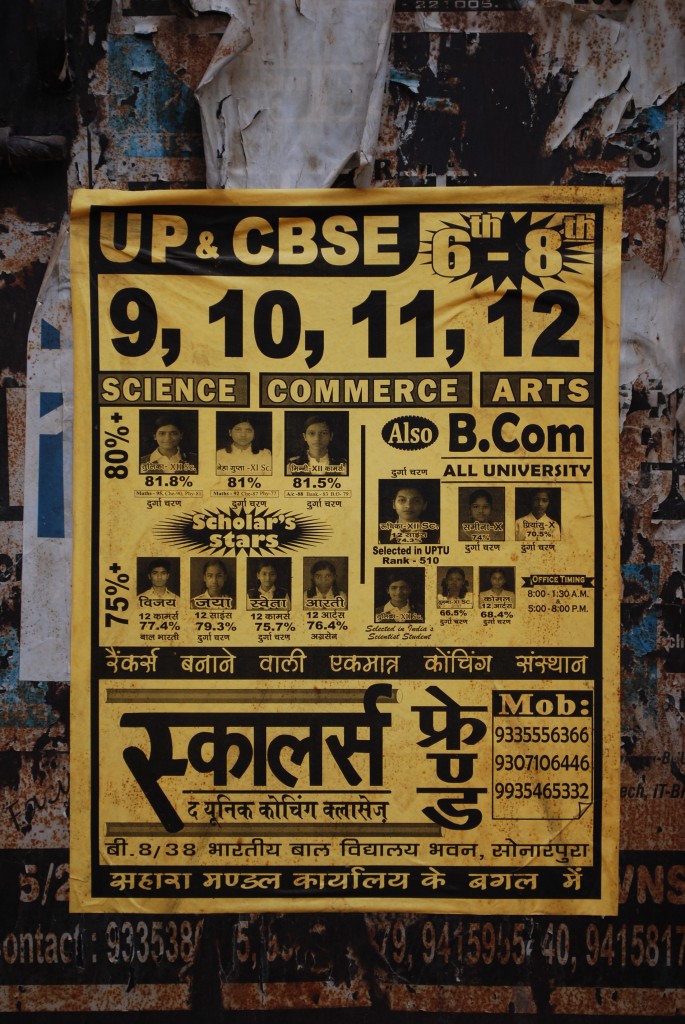

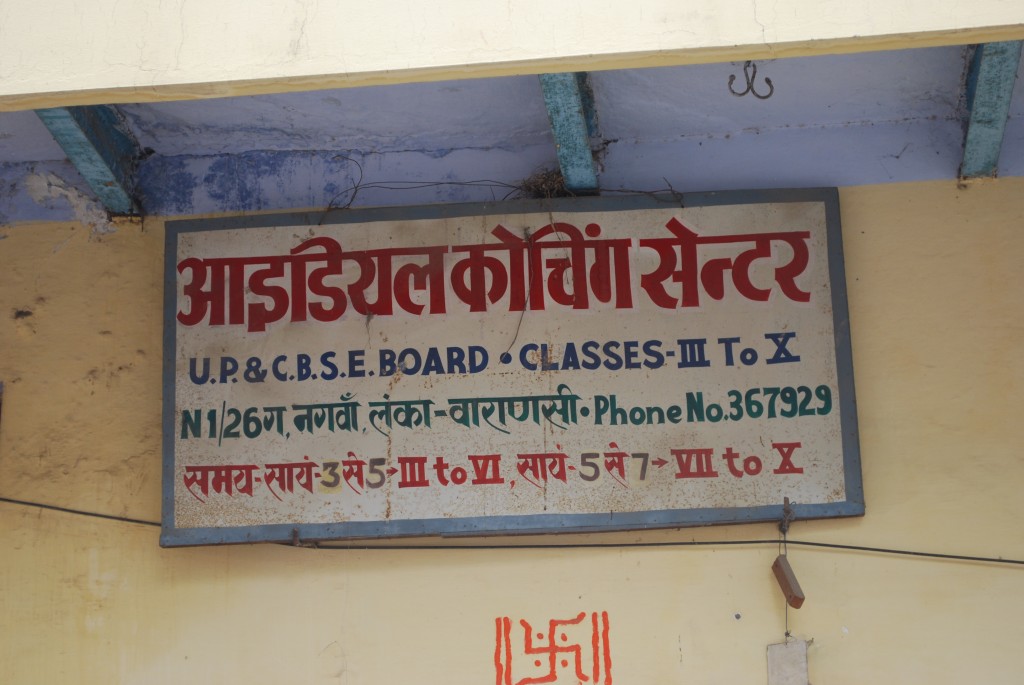

LaDousa helps us delve into “medium” as code by taking us along into school offices, classrooms, and homes, and by helping us decipher billboards that schools use to sell the experience they offer. He shows us how to listen to voices buried alive in personal and national histories. We learn how important cultural archeology is for making sense of education, both as a system and as an everyday experience.

—Krishna Kumar, from the Foreword

In many nations’ school systems, languages are not just options or possibilities in school. They also define schools. One might say that schools and languages are mutually constitutive: schools are places where languages gain a certain type of recognition, and languages are used to identify, talk about, and compare schools. When one type of school corresponds to a former colonial language that has gained a reputation for international communication and commerce, reflections on the educational pursuits of the self and others can become especially complicated—and often contradictory. The language that has come to represent the nation and for which one might have a great deal of reverence can exclude language varieties that one uses regularly. At the same time, the language that is so tied up in pride for the nation meets a grim fate as one progresses in the educational system. Another language presents possibilities in such higher educational pursuits; its salience has spurred on the proliferation of associated schools but has also fractured the promise of educational advancement.

The aim of this book is to illustrate some of the institutional and communicative structures that people in a small city in India struggled with as they engaged with schools and made sense of their school experiences. Especially important is that when people made sense of their school experiences, the intricacies of language difference were always relevant. Schools rested on and helped people to re-create language difference. In the same way, they entangled people in the contradictions of living in a postcolonial polity in which political-economic forces had offered a certain kind of education in a certain kind of language as an avenue for a livelihood marking something new. Indeed, language difference and inequality inform the very possibilities of schooling in a postcolonial polity, and people’s use of school to make sense of their past, present, and future implicates those people in cultural production.

—Chaise LaDousa, from the Preface

___________________________________________________

Chaise LaDousa is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York. His publications include House Signs and Collegiate Fun: Sex, Race, and Faith in a College Town (Indiana University Press, 2011) and articles in a number of peer-reviewed journals such as American Ethnologist, Journal of American Folklore, Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Journal of Pragmatics, and Language in Society.