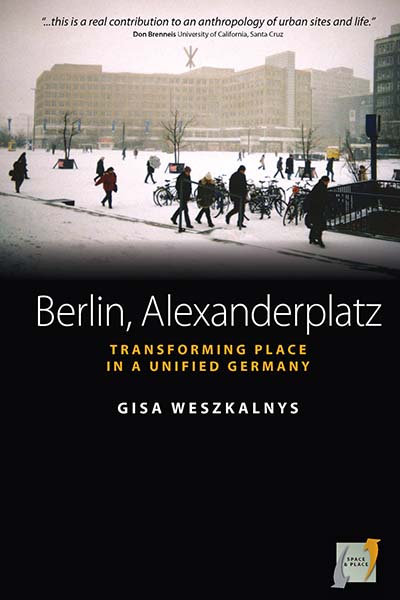

In 1990s Germany, Alexanderplatz, a centuries-old public square and transportation hub in Berlin, was seen a site in need of updating. Plans to improve the space, which were a part of post-unification revitalization, are central to Gisa Weszkalnys’ Berlin, Alexanderplatz: Transforming Place in a Unified Germany, which was published as a paperback late last year. Following is an excerpt from the volume, which gives insight into the collaborative process of the planned update.

____________________

In the early 1990s, Alexanderplatz was identified as a problem of urban design. A solution was to be found through an urban design competition, launched by the Senat’s Administration for Urban Development (SenStadt) in 1993. The winning design was to provide the basis for future constructions in the square. Following the competition, the Berlin Senat proceeded to establish a public-private partnership and to sign so-called urban development contracts with prospective investors.

After a series of public deliberations and revisions, the winning competition design was passed as a so-called Bebauungsplan in 1999, a legally binding plan, for Alexanderplatz. A special office, the Rahmenkoordinierung Alexanderplatz or Alexanderplatz Frame Coordination, was set up in 2000 to manage the incipient building works. Despite all the busy planning and organizing, however, the project experienced serious delays.

* * *

When I first began to investigate the Alexanderplatz project, there sometimes seemed to be no alternative to the kind of ‘after-the-fact theorizing’ that Sharon Macdonald (2001: 17, following Strathern 1992) has warned against in her analysis of the making of a London Science Museum exhibition. I was being presented with a coherent planning project that had been constructed from a set of clearly identifiable elements, and which was now enshrined in a legally binding plan. As Macdonald rightly argues, taking the finished product (the exhibition, the plan, etc.) as the analytical starting point unduly restricts anthropologists’ understanding of the complex processes and power relations implicated in its making. Further, such an approach tends to focus on the successes rather than the equally interesting failures, the ideas dropped on the way. We might even overlook how notions of ‘failure’ and ‘success’ are constructed in the first place.

Plans and projects are best understood as intersections of exchanges and meetings of different domains (human and non-human, technical and political, etc.), which are never complete (Latour 1996). Now, as I have already indicated, the new Alexanderplatz was not yet quite accomplished, but it was eagerly awaited. Its realization, as I will explain, seemed occasionally under threat in the early 2000s, partly related to a growing sense of a precipitate collapse of Berlin’s post-unification economic boom. First, however, I will discuss the persuasive rhetoric prevalent in the planning administration. I show how the administrators sought to persuade themselves and me that the plans for Alexanderplatz had everything needed to render it a success. They recounted the procedures that had been followed and the many legal requirements that had been met. They enlightened me on how the new Alexanderplatz fulfilled current planning goals and what rewards it would reap in the future. All this seemingly attested to the soundness and unassailability of the plans.

The administrators’ accounts typically revolved around three tropes. First, the optimization of the planning through the instrument of the competition; second, the comprehensiveness of the plan; and third, how the plan corresponded to Berlin’s current planning ‘philosophy’. I begin with how the competition optimized the planning.

Planning competitions, such as the one for Alexanderplatz in 1993, have enjoyed immense popularity in post-unification Berlin. Between 1992 and 1995, for example, 150 competitions were conducted. Some commentators have diagnosed a ‘competition fever’ (Lenhart 2001: 198). The competition, as one SenStadt employee explained, was a ‘well-established instrument of optimization’. What it was thought to optimize was not only the quality of the designs – by creating ‘competition’ amongst participating architects – but also the rationality, objectivity and accountability of the selection process. Itself a market-type metaphor (Carrier 1997: 3), it seemed that quality assurance and enhancement were in the nature of the competition itself (see Sennett 2003: 65). The most superb designs, however, are not automatically the most adequate ones.

The procedures surrounding public competitions like that for Alexanderplatz invoke additional authorities, beside the original architect or designer. There were also plenty of opportunities for citizens to give their opinion. Allowing others to inspect, and possibly rebuff, the judgements made, is thought to afford legitimacy to both the competition process and outcome. A clean procedure, I was assured, was better than the obscure decision of a senator based on something developed behind the administrative scenes. It would also ease the project’s subsequent acceptance amongst the public. For Alexanderplatz, sixteen architecture offices, of both national and international, East and West German provenance, were invited to enter. There was a carefully appointed jury, including – so I was told – not just ‘arty architects’ but persons with different kinds of expertise and voting power. As many as fifty people were asked to assume jury positions with such weighty titles as Fachpreisrichter and Sachpreisrichter (‘judges’ with architectural and other kinds of expertise respectively), Sachverständige (‘experts’, lit. ‘those who understand the thing’), Vorprüfer (‘pre-examiners’) and Gast (‘guest’).

When these men and women gathered to discuss the submissions, they supposedly bore in mind the myriad stipulations that a successful design would have to meet. These ranged from aesthetic qualities to its technical and financial feasibility, considered particularly important for a public project like Alexanderplatz. If there had been queries about the jury’s conduct, its members could have pointed to rules, tested and repeatedly amended over more than one hundred years, such as the ‘Principles and Requirements for Competitions’ set out by the Deutsche Städtetag (‘German Congress of Cities’). And lest misconduct should become rampant, there was the Architektenkammer (‘Architects’ Chamber’) entrusted with enforcing these rules (see Lenhart 2001: 198ff.; Strom 2001: 147ff.).

The perceived value of competitions may be understood in reference to the bureaucratic ethos, so critically reflected upon by Weber; or, alternatively, to more recent, and seemingly ubiquitous, demands for accountability, transparency and reflexivity on the part of policy makers, administrations, businesses and institutions of all kinds (Strathern 2000a). The very form the competition took ensured, in the eyes of many administrators, that it was a success. Competition results were claimed to rest on the scientific insights and rational judgments of numerous people who pledged allegiance to a certain professional ethos. Intensive participation procedures and numerous public discussions that accompanied the competition supposedly underscored the unassailability and viability of the plans. Prospective investors needed not fear further protest or defiance on the part of Berliners.

____________________________

Gisa Weszkalnys studied in Berlin and Cambridge and received her PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Cambridge. She is a Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Exeter and is conducting new research on oil developments in West Africa.

Series: Volume 1, Space and Place