Elizabeth Ward

On 17 May 1946, the Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft (DEFA) was officially founded. Over the course of the following four decades, the studio produced nearly 700 feature films, as well as hundred of animation and documentary films. By the time it was finally privatised and sold following German reunification, DEFA was one of Europe’s largest film studios.

Founded in 1946 and privatised and sold in 1992, DEFA both preceded the founding of the GDR and outlived it. For decades, East German film was overwhelmingly seen through the lens of state politics. As a state-owned studio, DEFA’s output was certainly impacted by domestic politics, above all as the result of so-called cultural ‘freezes’ and ‘thaws’ – periods of cultural orthodoxy and periods of relative liberalization – according to which the parameters of representation might shift. But to view DEFA films as a straightforward reflection of, or direct insight into, East German politics is to misunderstand the complexities not only of East German filmmaking practices, but also the variety and richness of DEFA’s output. As the director and cinematographer Roland Gräf later observed, ‘Art in the GDR always developed from friction, never pure affirmation.’

By the same token, we need to be wary of using ‘controversial’ and ‘subversive’ as synonyms. There were certainly high-profile examples of films that were removed from cinemas and films that resulted in the direct intervention of the state. Perhaps the most well-known example of this is the infamous Eleventh Plenum Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany in 1965. The plenum was originally intended as a celebration of East German economic policy, but filmmakers unexpectedly found themselves under direct criticism following attempts by the party leadership to divert attention away from the failure to bring about economic reform. Erich Honecker spearheaded the attack against filmmakers, accusing them of ‘sparking doubts about the policies of the GDR’ by promoting certain views and ‘tendencies’ that were ‘alien’ and ‘damaging to socialism’, of showing the relationship between the individual and party leaders as ‘cold and detached’ and of propagating ‘nihilistic, despondent, and morally subversive philosophies’. The result was the cancellation of nearly the entire year’s production output and the curtailment of several directors’ and film officials’ careers. Yet such overt instances of censorship were very much the exception in the GDR. Of course, we should not underestimate the role played by ‘self-censorship’: filmmakers understood what types of material would – and would not – receive approval. However, even when films did prove to be controversial, filmmakers were often seeking to make films that provoked discussion, rather than necessarily seeking to subvert the core principles of the GDR. Understanding the context in which DEFA productions were produced may serve as the starting point for our engagement with the films, but it should never mark its end point.

The DEFA’s feature film studios were located in Babelsberg, an area rich in film history. Formerly the 1920s and 1930s site of the UFA studios and today the location of the famous Babelsberg Film Studio, Babelsberg has always been associated with both German cinema and international filmmaking excellence. One of the most important developments in German film scholarship in recent years has been the confident reassertion of DEFA’s position within the nation’s film heritage. Over the past fifteen years, scholarly interest in DEFA films both within and outside Germany has increased markedly. Whether studies of genre films, co-productions, the studio’s history, key filmmakers or specific themes and subject areas, film scholars and historians have revealed the extent to which DEFA films were marked by aesthetic innovation, challenging treatments of subject material and networks of international circulation and collaboration. The growth in scholarly interest in DEFA films has been accompanied by the growing availability of both well-known and often forgotten productions, whether on DVD, through online streaming services or via the DEFA Stiftung’s YouTube channel. As we mark what would have been DEFA’s 75th anniversary, we can point to the rich scope of the studio’s output. Without doubt, some of the studio’s films do leave a problematic legacy, above all its explicitly political films. But to reduce DEFA films to little more than cinematic realisations of official political narratives is to simplify the complicated and often contradictory processes that shaped film production in the GDR, as well as to overlook the genuinely innovative images and storylines present in many productions. The DEFA film studio may be a closed chapter in German film production, but the legacy of its output continues to invite new viewings.

Elizabeth Ward is a Lecturer in German Studies and specializes in German film. She is a steering committee member of the German Screen Studies Network and has published on East German cinema, contemporary Holocaust film and twenty-first century German cinema.

Related Title

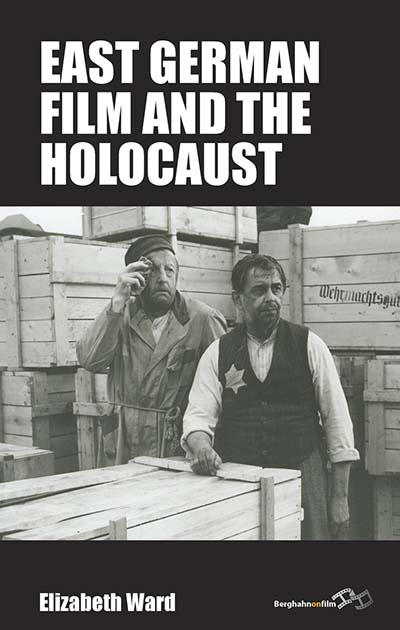

EAST GERMAN FILM AND THE HOLOCAUST

Elizabeth Ward

East Germany’s ruling party never officially acknowledged responsibility for the crimes committed in Germany’s name during the Third Reich. Instead, it cast communists as both victims of and victors over National Socialist oppression while marginalizing discussions of Jewish suffering. Yet for the 1977 Academy Awards, the Ministry of Culture submitted Jakob der Lügner – a film focused exclusively on Jewish victimhood that would become the only East German film to ever be officially nominated. By combining close analyses of key films with extensive archival research, this book explores how GDR filmmakers depicted Jews and the Holocaust in a country where memories of Nazi persecution were highly prescribed, tightly controlled and invariably political.

Purchase the eBook

Stay connected

For updates on our Film and Television Studies list as well as all other developments from Berghahn, sign up for customized e-Newsletters, become a Facebook fan, follow us on Twitter and Instagram, and listen to our podcast, Salon B, on Spotify.