In Michaela Schäuble’s ethnographic account, Narrating Victimhood: Gender, Religion and the Making of Place in Post-War Croatia, she examines religion, gender relations, and nation building in the newly independent country. Following, the author gives readers a photographic glimpse into the Republic of Croatia after its war for independence. See the other photos in the gallery here.

In Michaela Schäuble’s ethnographic account, Narrating Victimhood: Gender, Religion and the Making of Place in Post-War Croatia, she examines religion, gender relations, and nation building in the newly independent country. Following, the author gives readers a photographic glimpse into the Republic of Croatia after its war for independence. See the other photos in the gallery here.

________________________________

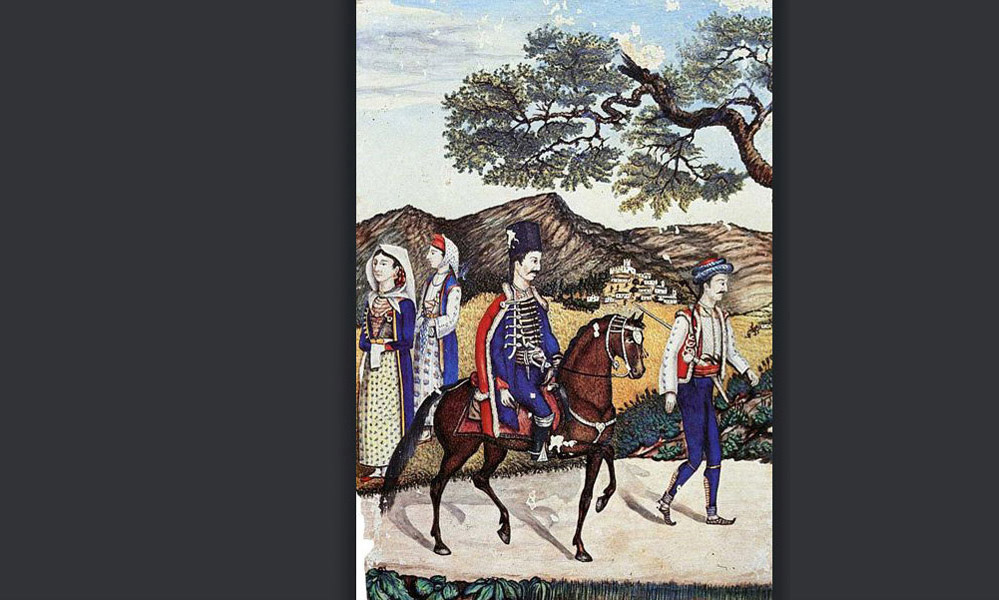

The Sinjksa Alka or ‘Alka of Sinj’ is a knight tournament that has been held in the Dalmatian town of Sinj since the 18th century in commemoration of the victory over attacking Ottoman troops and the alleged Marian apparition in 1715. Drawing upon the medieval tradition of tournaments and horsemanship competitions (carousels), the Alka is held in historic costumes and has been declared a historical monument of the highest order and has been inscribed in UNESCO Intangible Heritage lists in 2010. Only men born in Sinj can take part in this game of skill as horsemen [alkar(Sg.), alkari(Pl.)], and it is considered a great honour to win the Alka tournament. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

__________________________

A monumental size dummy of former chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), Carla del Ponte, is burnt during Carnival in Croatia in 2005. For the Croatian public the contrast to the virtuous male national hero is constructed as a negatively connoted non-Croat female figure. This anti-hero is Carla del Ponte. She was frequently labelled as ‘the whore in The Hague’ [kurva u Haagu] or as ‘Carla, the whore’ [kurva Carla] by my (male) interlocutors – thus transforming a political issue into a sexualised, misogynist discourse. Photo: Keystone

_________________________

A placard of Ante Gotovina next to a figure of the crucified Christ. The slogan Heroj a ne zločinac! [Hero, not (war) criminal] is also commonly used in protests, primarily led by Croatian war veterans and right-wing associations. The assertion of Gotovina’s ‘unjust indictment’ and the consequent refusal to cooperate with the ICTYcontained therein, are closely linked to a more general Eurosceptical attitude. Many Croats referred to the Gotovina and Norac convictions as submitting to blackmail and perceived them as sacrifices Croatia was forced to make in order to join the European Union. This perception makes the ex-generals not only scapegoats but martyrs in the classical sense. Photo: Paul Henley

_________________________

A placard of ex-general Ante Gotovina, reading “War Hero, Croatian Legend,” that was put in Sinj by the “Croatian Homeland War Volunteer Veterans Association.” Ante Gotovina has become the epitome of Croatia’s dealing with war crime allegations. In 2001, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) indicted the former lieutenant general Ante Gotovina on a number of war crimes and crimes against humanity charges for his involvement during and in the aftermath of the military offensive ‘Operation Storm’ in 1995. After spending four years in hiding, he was captured on Tenerife in December 2005. After Gotovina’s transfer to the court in The Hague, the process of his ‘sanctification’ in Croatia proceeded apace. Particularly in Dalmatia, people continued to refer to him as a messianic figure to whom they owe Croatia’s independence and who has thus become the main target of Europe’s malice. In April 2011, he was found guilty on eight of the nine counts of the indictment and sentenced to 24 years of imprisonment. This caused huge protests throughout Croatia — Ante Gotovina’s arrest, his extradition to The Hague and his eventual guilty verdict were perceived as a continuation of ‘historical injustice’ in the course of which the international community has ostensibly wronged and repeatedly victimised Croatia. It is in this context that one has to understand the enthusiasm and sense of victory that seized the whole country when in November 2012 the initial verdicts against Gotovina were overturned. In a very surprising decision, by a 3–2 majority in the UN court’s five-judge appeals chamber, Gotovina was acquitted of all charges on the basis of individual responsibility for the crimes committed. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

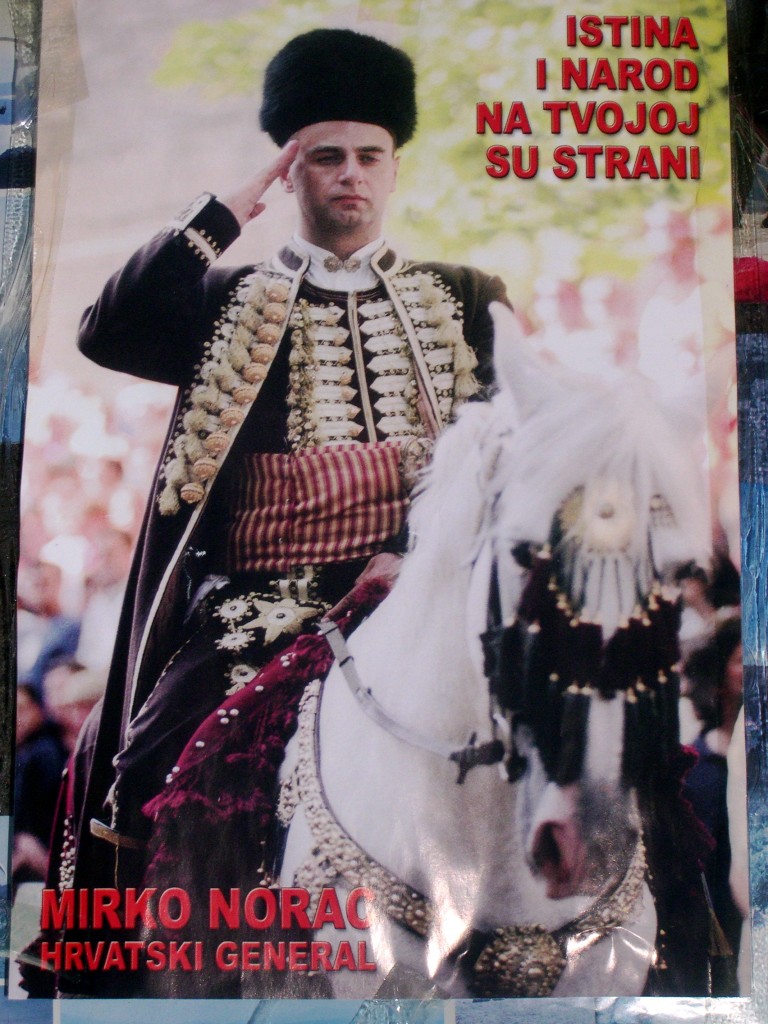

Placard displaying “The truth and the people are on your side.” From 2001 to 2005 former Croatian general Mirko Norac was the honorary Duke of the Alka games. Norac was the first Croatian general to be convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity during the Homeland War. In 2001 he was sentenced to twelve years’ imprisonment by a court in Rijeka. After being pronounced guilty of involvement in the ‘Gospić massacre’ in which more than a hundred local Serb civilians were murdered by men under his command in October 1991, powerful political anti-cooperation groups and war veteran organisations organised huge rallies in his support. Born in Otok, a small village near Sinj, Mirko Norac is closely connected to the region. After his trial, Norac reputedly said that the first thing he would do after his expected release was to participate in the Alka tournament. This statement illustrates the significance of the games as a key symbol of (military) honour and regional pride. However, after his release he did not appear at the 2012 Alka tournament. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

A disability sticker on a car signifying that the driver is a war invalid. The number of soldiers who participated in the Homeland War (1991-1995) has long been the subject of controversy in Croatia, but the number of Croatian homeland veterans who are currently disability pensions beneficiaries amounts to approximately 52,000. The official term for Croatian war veterans, branitelji, translates literally as ‘defenders’ (from braniti, ‘to defend’) and reflects the official perception of the Croatian military actions during the Homeland War as mere defence operations. Highlighting the defensive character of Croatian warfare is a viable strategy of distancing oneself from the committed crimes, since self-defence is considered the most legitimate of all acts of violence. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

__________________________

Marija T. is the mother of the boy who first saw the Mother of God when she allegedly appeared here in 1983. Marija demonstrates where the Mother of God sat when she first appeared, combing her long blonde hair. Marija’s own corporeal and tactile re-enactment of the Gospa’s behavior was as much an attempt to show us as it was an attempt to understand herself what had occurred here in 1983. And although she had not seen the apparition with her own eyes, she seems to be able to (re-)feel the presence of the Gospa through the sensory impulse of imitating her. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

To the present day, Marija pays daily visits to the shrine to communicate with the Madonna. Praying, for her, is a sensory and an aesthetic experience: the way she touches and caresses the statue conveys a deep love and connectedness. Marija also tells that the statue occasionally sheds tears. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

A Marian altar hidden in the woods in the small village of Gala, near Sinj. In 1983 the Mother of God allegedly appeared to a group of children. Despite all parallels, this apparition site did not develop into an internationally acclaimed pilgrimage location like Međugorje in neighboring Bosnia-Herzegovina, but remained a locally constrained and highly contested site of worship. The Catholic church never acknowledged the apparitions, but a local cult prevails. Once every year, a mass is held by a local Franciscans and hundreds pilgrims from all over Croatia and Italy travel to the apparition site in Gala. The Marian statue was donated by a group of pilgrims from Italy but the altar and memorial chapel was not erected until 2001. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

An elderly women displays two posters attached to a wooden handle. One of the placards is a replica of the Gospa Sinjska with the inscription Čudotvorna Gospe Sinjska moli za nas! [Miraculous Lady of Sinj, pray for us]. The lower one depicts General Mirko Norac, and provocatively reads Ako smo slobodni, ne dajmo osloboditelje! [If we were free, we wouldn’t extradite our liberators!]. Norac, a local of Sinj, was the first Croatian general to be convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity during the Homeland War (1991-1995). The slogan is meant as a protest against his prison sentence and the extradition of other former generals to the criminal tribunal in The Hague. This combination of creed and political commentary points towards the close connection between the veneration of religious figures and militarised hero-worship in post-war Croatian society. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

After the open-air “Mass for the Victims of Communist Atrocities” people gather for picnics and sheep are slaughtered for the barbecue. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

Wreaths commemorating the “Victims of Communist Atrocities” are laid at the jama. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

The “Mass for the Victims of Communist Atrocities” was held in autumn 2005 at a natural crevice [jama]in the mountains surrounding Sinj. The area is full of massacre sites and mass graves – dating from different epochs and conflicts – that had previously been concealed under Tito’s regime. With the unearthing of mass graves in the early 1990s, notions of ancestry and territory were drastically re-evaluated, public resentment about suppressed memories of past atrocities was fuelled, and previously suppressed ethno-national tensions increasingly started to escalate. In this sense, “dead body politics,” as Verdery calls the phenomenon of turning the dead into political messengers, are key to understanding how past atrocities were revived and fuelled the (ethno-)political consciousness of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The unearthing of previously unacknowledged massacre sites occurs in the region even now, and the commemoration of “victims of communist atrocities” at a jama in the limestone karst mountains that surround Sinj continues to stir strong emotions and connects narratives of ‘historical injustice and concealment’ to specific places and landscapes of victimisation. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

In 1950 Marshal Tito paid his first personal visit to Sinj. In 1978 he was proclaimed Honorary Tournament Master and when he was presented with the emblems by a delegation from Sinj, he was allegedly very moved, saying: “Holding the Alka tournament as a souvenir of a victory over the Turkish invaders has profound significance for our history and represents an important manifestation not only for your region but for socialist Yugoslavia as a whole. I am glad you still celebrate regularly that victory when the people of Sinj and the Cetina district took up arms against the invader. The memory lives on among our people, always transmitted to the next generation.” The Alka horsemen and their squires paid their last respects to Josip Broz Tito when they stood as honour guard by the catafalque at his funeral on 5 May 1980. Photo: Etnografski Muzej Sinj

_________________________

Historical image of the Sinjska Alka. Photo: Etnografski Muzej Sinj

_________________________

A brass band playing marching tunes parades along the narrow alleys of the town. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

A brass band playing marching tunes parades along the narrow alleys of the town. Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_________________________

The squires [momak(Sg.), momci (Pl.)] represent the foot soldiers who fought in the battle against the Turks. They are brawny moustachioed local men of almost two metres height, who march uprightly and proudly in time to the music glancing neither right nor left. They wear the traditional folk costume of the Centiska Krajina with red bonnets of Illyrian origin. Over their shoulders they carry long flintlock guns, a flint pistol and a dagger that is tucked into their waistband, called “the serpent’s nest.” Photo: Michaela Schäuble

_______________________________________

Michaela Schäuble is Lecturer in Social and Visual Anthropology at the University of Manchester. Since 2011 she has held postdoctoral fellowships at the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard University and the Institute of Advanced Studies at Bologna University.

Series: Volume 11, Space and Place