Sasha Disko

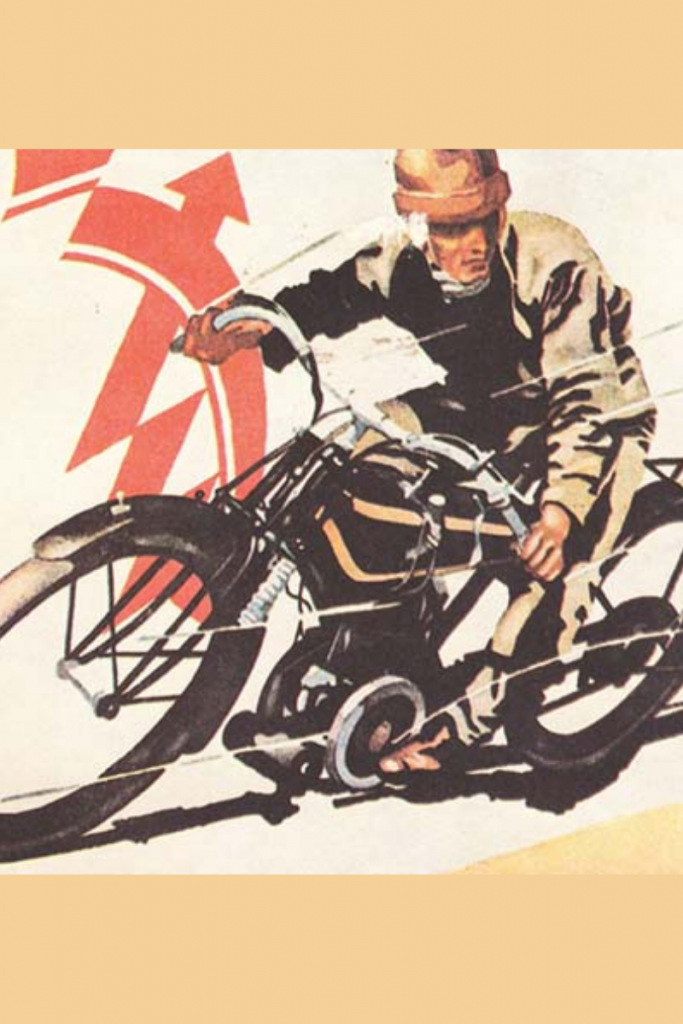

In celebration of World Motorcycle Day (21 June), we are featuring the following excerpt from Sasha Disko’s THE DEVIL’S WHEELS: Men and Motorcycling in the Weimar Republic.

Someone, or something, sowed the flaming desire in your young male heart to become a disciple of motor sport. . . . Your desire was initially borne of envy at the daily experience of seeing a friend race noisily by on his jalopy, while you must travel cumbersomely and slowly by foot. . . . The desire eats and gnaws and nourishes itself from thence on within your breast . . . Fills all of your senses and thoughts . . . Follows you in your dreams.

—Alexander Büttner, Motorrad-Sport, -Verkehr und -Technik

Loosely crafted in the form of a Bildungsroman, Alexander Büttner’s short story from 1924 portrays a male protagonist in his journey from pedestrian to motorcyclist, culminating in his evolution into a “real man.” Sparked by an irresistible desire, the “motorcyclist’s development” is punctuated by acts of consumption, first by ordering catalogs, then in purchasing a motorcycle. Once a motorcycle owner, a number of accessories suddenly appear indispensable to the rookie motorcyclist. “You mount the bike and race through the city . . . and all the while you notice that a hundred things are missing that you absolutely need: a gruff horn, an odometer, a speedometer, and especially electric lights, and good tires . . . spare parts and a well-sprung pillion seat.” Participation in consumer culture was a requirement for the overwhelmingly male owners of motor vehicles during the Weimar Republic. Yet most contemporary observations, as well as subsequent analyses, have consistently linked consumption to femininity, while studies of masculinity during the Weimar Republic have focused predominantly on militarized masculinity as the hegemonic form. Indeed, in Büttner’s short story and in the discourse of motorcycling as a whole, proper masculinity was rhetorically disassociated from conspicuous consumption. The act of masculine consumption was concealed behind the twin pillars of modern manliness: production and possession. As the motorcyclist progresses through the stages from “novice” (intoxicated with speed until he crashes) to “connoisseur” (a gourmet of beauty in both landscapes and motorcycles), he is not depicted as merely consuming passively. Instead, the motorcyclist is portrayed as mastering time, space, and the machine. The emphasis is on acquiring skills and knowledge, rather than new gadgets or accessories.

While the “motorcyclist’s development” may appear idiosyncratic at first glance, the themes Büttner addresses are emblematic of modernity and masculinity in Germany during the first decades of the twentieth century. Although the dream world of mass automobility was in its infancy, increasingly affordable, domestically manufactured motorcycles swelled the ranks of German motorists. The number of two-wheelers, including two-stroke motorcycles with low engine capacity, steadily rose, surpassing the number of automobiles on German roads in 1926. By the end of the 1920s, with motor vehicle registrations totaling well over a million, motorcycles outnumbered automobiles by three to two. While individual automobile ownership continued to be a privilege of the upper classes, by the late 1920s the working classes were taking to motorcycling in droves. Skilled and unskilled laborers, alongside new white-collar workers so astutely analyzed by Siegfried Kracauer in The Salaried Masses: Duty and Distraction in Weimar Germany, were able to participate in motorization through buying mass-produced two-wheelers, sometimes making use of layaway plans or the extensive used-motorcycle market. This book explores how the everyday choices that men and women made expressed their desires to partake in the social and spatial mobility offered by motorization, and how their actions also produced and reflected anxieties about inhabiting an increasingly elastic and plastic world.

About the book

THE DEVIL’S WHEELS

Men and Motorcycling in the Weimar Republic

Sasha Disko

“A fine study of the gendering of motorcycles in the inter- war years, Sasha Disko’s The Devil’s Wheels offers an important interpretation of a mass-produced technology, the motorcycle, and how it came to embody masculinity as well as new forms of consumerism.” • American Historical Review

During the high days of modernization fever, among the many disorienting changes Germans experienced in the Weimar Republic was an unprecedented mingling of consumption and identity: increasingly, what one bought signaled who one was. Exemplary of this volatile dynamic was the era’s burgeoning motorcycle culture. With automobiles largely a luxury of the upper classes, motorcycles complexly symbolized masculinity and freedom, embodying a widespread desire to embrace progress as well as profound anxieties over the course of social transformation. Through its richly textured account of the motorcycle as both icon and commodity, The Devil’s Wheels teases out the intricacies of gender and class in the Weimar years.

Purchase the eBook

Stay Connected

For updates on our History list as well as all other developments from Berghahn, sign up for customized e-Newsletters, become a Facebook fan, follow us on Twitter and Instagram, and listen to our podcast, Salon B, on Spotify.