Thomas Pegelow Kaplan and Wolf Gruner

Raul Hilberg’s path-breaking 1961 study The Destruction of the European Jews rightfully remains on the reading list of any serious student of the Holocaust. Nonetheless, Hilberg’s insistence on European Jews‘ alleged “almost complete lack of resistance” has been subjected to frequent scholarly criticism. He partially based this claim on a cursory reading of petitions: “Everywhere, the Jews pitted words against rifles” and “everywhere they lost.”

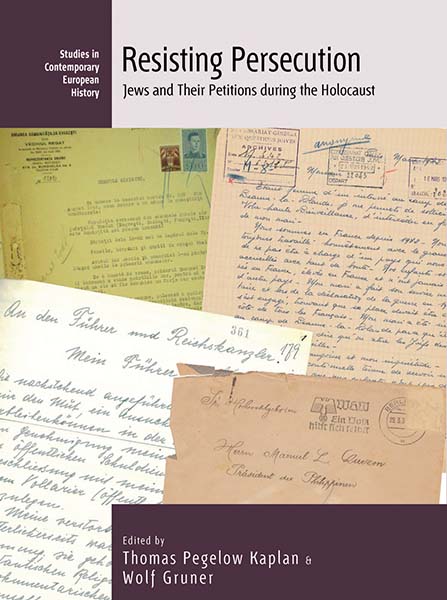

Hilberg’s brash treatment of Jewish petitions along with the relatively little attention Holocaust scholarship has paid to these practices has struck the co-editors of Resisting Persecution: Jews and their Petitions during the Holocaust, the present volume, as highly problematic. During many years of archival work in the Americas, Israel, Europe and beyond, we have come across thousands of Jewish entreaties. Even while going through the Presidential Papers of Manuel L. Quezon at the National Library of the Philippines in Manila in 2014, Thomas Pegelow Kaplan found a cache of petitions of Jews desperate to flee Hitler’s Europe.

It was, however, not just the sheer number of Holocaust-era petitions that pointed to their significance. Petitioning was a long-established practice accessible and used by Jews of all socio-economic and educational statuses across the European continent. Yet, with the new volume, the co-editor wanted to initiate fresh research looking into the specific situation to which Jewish women and men were reacting by authoring petitions during the Holocaust: authoritarian regimes and their oppressive and eventually genocidal practices.

In Nazi Germany, France, Romania, Hungary and elsewhere Jews actively opposed national anti-Jewish policies and local measures. Their entreaties ranged from requesting an exemption from a pending deportation penciled on a small piece of paper that its author gave to the head of the Council of Elders in the street of the Lodz Ghetto to typewritten formulaic letters to Nazi authorities for racial re-classification and very elaborate entreaties such as Rabbi Jacob Kaplan’s appeal against Vichy France’s second Statut des Juifs addressed to Xavier Vallat, Vichy’s Commissioner General for Jewish Affairs.

For this volume, we called upon junior and senior Holocaust studies scholars who are specialists for various regions and countries to shed light on the complex petitioning networks and practices in dozens of languages across the continent and beyond. Some of them had worked on this topic before, some had not, but all were aware of the abundance and neglect of Jewish petitions during the Holocaust. As the new research on various countries in this volume demonstrates, many petitions were not just addressing injustices or requesting the abolishment of anti-Jewish measures, but also re-claiming their rejected identities as citizens, taxpayers and contributors to the culture of the homeland.

Especially after the onset of the genocide, writing petitions exposed the Jewish authors along with their families to potential repercussions. With the previous constitutional safeguards removed, this kind of negative reaction was even more likely when petitioners challenged or directly rejected anti-Jewish measures.

The very notion of writing Holocaust-era petitions in vain needs to be reassessed. Contesting persecution and reclaiming identities already were courageous achievements, especially in light of the asymmetric power relations in Nazi-controlled Europe. Moreover, some petitions achieved their authors’ goals such as the release of imprisoned persons. Others even reshaped persecution matters. In 1944, entreaties in the Budapest Ghetto led to the creation of so-called “mixed houses”, where Jews could stay in their homes next to gentile tenants, instead of being relocated. Even the processing of ultimately declined petitions could offer much-needed time for alternate responses such as flight preparations and, thus, enable the petitioners’ survival until liberation. Indeed, petitions did matter!

Our new research on the Greater German Reich, including the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, France, Romania and Hungary illuminates how European Jews resorted to a broad range of entreaties to reassert their agency, reclaim their public identity and contest or even resist the mounting discrimination and persecution. Petitioning constituted an overlooked, yet crucial form of responding to fascist onslaughts that powerfully proves that Jewish men and women – from ordinary community members to prominent leaders – were anything but passive victims.

For all its new insights, the first volume on this topic cannot provide an exhaustive examination of such a widespread phenomenon. Jewish entreaties in the German-occupied territories of the Soviet Union, the Netherlands or in Greece, for example, are not touched upon. Hence, this volume intends to prompt more research on this understudied and misconceived, yet fascinating, complex and illuminating subject of Jewish petitioning as acts of contestation and resistance.

Thomas Pegelow Kaplan and Wolf Gruner are the editors of Resisting Persecution: Jews and Their Petitions During the Holocaust. This volume offers the first extensive analysis of petitions authored by Jews in nations ruled by the Nazis and their allies. It demonstrates their underappreciated value as a historical source and reveals the many attempts of European Jews to resist intensifying persecution and actively struggle for survival. It is the twenty-fourth volume in the Contemporary European History Series.

To learn more, read the introduction.

Purchase RESISTING PERSECUTION and all other Berghahn Books for 30% off with code SUMMER20 (offer valid via our website until 1 September 2020).