Read an excerpt from Marek Haltof’s POLISH FILM AND THE HOLOCAUST: Politics and Memory.

On April 19, 1943, the Warsaw ghetto uprising began after German troops and police entered the ghetto to deport its surviving inhabitants. Learn more about the history of this fierce act of resistance by reading the entry in the USHMM’s Holocaust Encyclopedia.

The following is excerpted from Marek Haltof’s POLISH FILM AND THE HOLOCAUST: Politics and Memory.

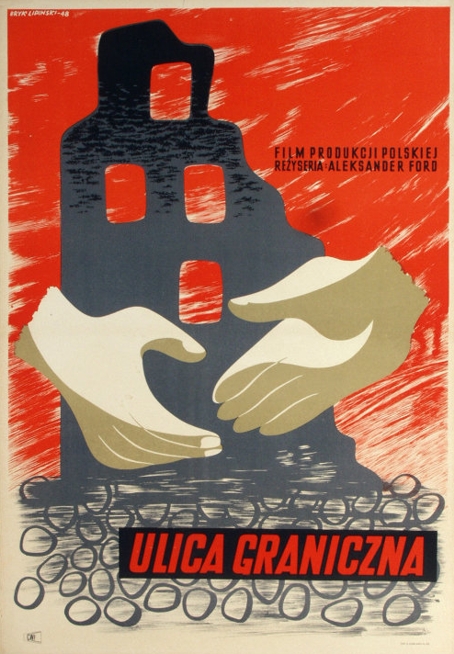

Commemorating the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in Border Street (1949)

[Chapter 3, pp. 56-57, 60-62]

To understand the difficulties faced by [Aleksander] Ford, it is imperative to see the political context of his film, namely how the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising had been commemorated in Poland. The first memorial was unveiled in Warsaw on 16 April 1946, and was placed where the uprising started. Designed by Polish architect Leon Marek Suzin, the monument was dedicated (in Polish, Yiddish, and Hebrew) “To the memory of those who died in unparalleled and heroic struggle for the dignity and freedom of the Jewish nation, for free Poland, and for the liberation of mankind—the Jews of Poland.” Nathan Rapoport’s Warsaw Ghetto Monument, which was unveiled to full military honors on 19 April 1948, five years after the uprising began, is arguably better known. The heroic-tragic figures on the front of this eleven-meter-high monument represent different ghetto fighters. The composition clearly emphasizes armed resistance and martyrdom rather than the memory of those who were exterminated in the ghetto and in the concentration camps. The inscription on it, “To the Jewish nation—to its fighters and its martyrs,” makes this notion apparent. The reverse side of the monument, sometimes missed by visitors, represents the suffering, deportations, and death.

It has to be stressed that the first memorial commemorating the 1944 Warsaw Rising was built as late as 1989, after the fall of communism. This fact certainly did not help Polish-Jewish relations. A Warsaw-based journalist Konstanty Gebert aptly writes that “these Jewish memorials reminded many of the Poles of the monument to the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, one year after the Ghetto Uprising, which had not been built. The 1944 struggle, led by the non-communist underground army (Armia Krajowa, AK), had become almost a nonevent in Polish communist historiography. The speedy commemoration of the Jewish Uprising, coupled with the official non recognition of the Polish one, provided grounds for years of bitter feelings.” Taking this into account, one may only agree with Omer Bartov who fittingly writes that Ford’s Border Street served “two contradictory purposes”: “First, it was an opportunity to extol Jewish heroism, showing that the Jews were ‘just as heroic’ as the Poles and asserting that Jews and Poles had united in resisting the Germans. Second, it served as an ersatz depiction of what most Poles experienced as a far more traumatic, but equally heroic event, the Polish Warsaw Uprising of August 1944.” Released in 1957, Andrzej Wajda’s breakthrough Kanal (Kanał) became the first film about the Warsaw Rising, narrating the story of a Home Army unit that manages to escape German troops via the only route left —the city sewers— in which the majority of the fighters meet their deaths.

The Warsaw Ghetto Monument reflects a general attitude toward martyrdom and victimhood in the late 1940s. Writing about the American attitudes toward the Holocaust, Peter Novick states: “Whereas nowadays the status of victim has come to be prized, in the forties and fifties it evoked at best the sort of pity mixed with contempt. It was a label actively shunned.” He also notes that in the late 1940s several prominent American Jewish organizations objected to a proposed Holocaust memorial in New York City: “They were concerned that such a monument would result in Americans’ thinking of Jews as victims: it would be ‘a perpetual memorial to the weakness and defenselessness of the Jewish people’; it would ‘not be in the best interests of Jewry.’”

***

Border Street opens with credits over the shots of wartime Warsaw ruins. After the credits the camera continues to capture images of destruction. The voiceover commentary introduces the setting of the film:

Streets changed into cemeteries. Ruins, burned down places. So many of them you can still find in Warsaw. The action of our film takes place on one such street. Let us call it Border Street, although it could be Długa, Bielańska or Świętokrzyska. We don’t want to determine its real name. We do intend only to show a small fragment of its history, the history of its modest inhabitants, little people, children, or practically children.

This initial comment suggests that “Border Street” is a fictional street that could be anywhere in Warsaw, thus enhancing a deeply symbolic, universal meaning of the film. There was, however, a real “Border Street” (Ulica Graniczna) in Warsaw, situated alongside the ghetto wall, and close to one of the entrances to the ghetto.

The film’s action moves briefly to a period preceding the September 1939 invasion of Poland and swiftly introduces several different Polish and Jewish families living in a Warsaw apartment building on Border Street. Among them is the Polonized Jewish doctor Józef Białek (Jerzy Leszczyński) and his daughter Jadzia (Maria Broniewska); a bank employee Kazimierz Wojtan (Jerzy Pichelski) with family, who is portrayed as a proud nationalist Pole; Kuśmirak, an opportunist shopkeeper who runs a café with his family; the good natured, working-class Cieplikowski (Władysław Walter) with his son Bronek. The basement of the building is inhabited by the Libermans: an orthodox Jewish tailor Liberman (Władysław Godik) and his family, including an assimilated socialist worker Natan (Stefan Śródka) and his nephew Dawidek (Jerzy Złotnicki).

The initial scenes of Ford’s film also introduce the anti-Jewish attitudes of several Poles. For example, Dawidek is victimized by Polish boys when he clumsily tries to join them for a soccer game. Wojtan also comments that “of course, there will be no war. Hitler will never dare. The Jews only encourage such gossip to make better business,” and forbids his son, Władek, to play with Dawidek. However, Wojtan’s wife defends Dawidek by saying that he “is a good child although he is Jewish,” and she calls the Libermans “decent people.”

With the war imminent, Wojtan puts on his officer’s uniform and is surprised to see Natan also wearing a Polish soldier’s uniform. In another scene, Cieplikowski’s comment, “I’m telling you: there will be no war,” is followed by images of German planes over Warsaw. An abrupt cut moves the action to occupied Warsaw and introduces a symbolic image, often employed in Polish cinema, of a wounded Polish soldier watching the victorious German troops marching on the streets of Warsaw. The subsequent occupation changes relations among the families on Border Street. In an almost farcical scene, Kuśmirak (played by a Czech actor Josef Muncliger) defines himself as a Volksdeutsch in purely visual terms at a barber store, by trimming his Piłsudski-like moustache and changing his hairstyle to resemble Hitler (“The times have changed,” he proclaims to a surprised barber). Later, Kuśmirak (now Kushmirak) takes advantage of his privileged position and blackmails Dr. Białek, threatening to reveal his Jewish identity. He forces him to move to the ghetto and takes over his spacious apartment.

While showing differences between the treatment of Poles and Jews by the Germans, Ford constantly accentuates the need for unity and common struggle with the occupier. Wojtan comes to the conclusion that “the Jews are not all alike, and we have our own Kuśmiraks, too.” When Liberman comments that “terrible times are coming for the Jews,” Natan responds emphatically, “not only for the Jews.” After learning about the creation of the ghetto, Liberman says that “maybe it will be better for the Jews to be separate.” When his daughter supports him (“But at least in the ghetto, we shall all be equal”), Natan responds in the following way: “Oh yes, they will exterminate all of us equally. Don’t you see? They want to separate us from the Poles. It will be easier to eliminate us and the Pole … It is their policy. In the POW camp people were saying that we should be together. To fight!” When the fatalistic Liberman ridicules Natan’s desire to fight, he responds that the Jews will fight even with bare fists (and his gesture looks as if taken from a propagandist war poster): “The Poles will surely fight and we should go with them.”

About the book

POLISH FILM AND THE HOLOCAUST

Politics and Memory

Marek Haltof

Choice Outstanding Academic Title 2012

“In this excellently researched, highly informative survey of Polish films about the Holocaust, Haltof… expands on a chapter in his valuable Polish National Cinema… His measured assessments, conveyed in clear, accessible prose, are rooted in an enviable command of both the relevant production documents and important secondary literature. The select list of relevant films and television programs is very useful. The ample notes and fine bibliography incorporate many Polish sources as well as all the available literature in English.” · Choice

Available in eBook and paperback

Request an e-inspection copy