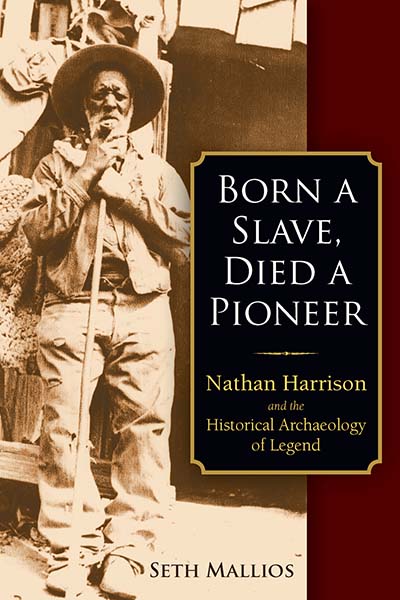

We’re pleased to present an excerpt from the introduction to Born a Slave, Died a Pioneer: Nathan Harrison and the Historical Archaeology of Legend by Seth Mallios. For a limited time, receive 25% off the paperback with code MAL308.

Nathan Harrison, an African American born into slavery in Kentucky decades before the Civil War, endured some of the most treacherous times in US history for anyone who was not white. Despite this, he grew into a permanent and prominent fixture thousands of miles fro his birthplace on a remote mountain in Southern California. Confronted with unfettered violence and bigotry in nearly every stage of his life—be it enslavement in the Antebellum South as a child, the hazardous trek across country as a subjugated teenager, Gold Rush exploitation as a young man, or the chaos of the Wild West as a newly emancipated free person—Harrison survived, persevered, and adapted. Although he ultimately lived alone, high up on Palomar Mountain in rural San Diego County for nearly half a century during the late 1800s and early 1900s, Harrison was deeply enmeshed in multiple local communities, including nearby Indigenou s groups, an extensive network of Mexican ranchers, and burgeoning Anglo populations in both rural and urban San Diego. Harrison did not sound, look, or act like any of his Southern California neighbors during his lengthy time in the region. Despite these pronounced diff erences and the lethal racial turmoil of the early US period in California, he gained widespread acceptance and was celebrated by his contemporaries for his extraordinary longevity, resourcefulness, regional knowledge, and charming demeanor.

Regardless of this past acclaim, most people alive today have never heard of Nathan Harrison. Those relatively few individuals who do recognize his name have likely encountered a wide array of tall tales, rife with far-fetched fabrication. While Harrison’s actual life story was a microcosm of the diverse cultural heritages and volatile histories of the nineteenth-century United States, a wealth of enticing exaggerations with tantalizingly unverified secondhand details have elevated his already significant biography into something more. They exalt Harrison, transforming this unsung migratory laborer of humble origins into a legendary western trailblazer and an enduring American pioneer. As such, Nathan Harrison has become larger than life.

The list of entertaining yet oĞ en highly inaccurate anecdotes about Harrison is so lengthy and broad that it covers nearly everything from his time in bondage before the Civil War to his later years at a rustic cabin high up Palomar Mountain in the southwest corner of the United States. Below is a sampling of some of the most conspicuous claims that were found in the historical research about him. Allegedly, Nathan Harrison:

– perilously escaped slavery, floating down the Mississippi River in the 1840s,

– fought with Frémont’s Battalion in the Bear Flag Revolt in the summer of 1846, helping the United States defeat Mexico and acquire California,

– joined the Mormon Battalion in 1846–47 as it made the longest infantry march in US history,

– sailed in treacherous waters around South America’s Cape Horn on the way to California in 1849,

– jumped ship at San Pedro (Los Angeles) in the 1850s as a fugitive slave,

– encountered notorious gold-country bandit Joaquin Murrieta in 1853,

– drove an ox team with the first wagon train over Tejon Pass in 1854, opening the primary route to Southern California,

– narrowly averted being scalped by tomahawk-wielding Native Americans in 1864 while traveling via covered wagon from Missouri to California,

– had multiple Southern California Indian wives in the 1880s,

– was the consummate Wild West mountain man—he rode a radiant white horse, could tame any wild stallion, had “owl eyes” (the ability to see in total darkness), and once killed a mountain lion measuring over 14 feet in length,

– hid a sizable stash of gold from his mining days near his cabin; it has never been found,

– lived to be 107 years old, finally succumbing to natural causes in 1920, and finally . . .

– to this day, Nathan Harrison’s ghost morosely wanders his Palomar Mountain home, distraught that his body was placed in an unmarked grave, over 100 miles away from his beloved hillside homestead.

Some of these embellished stories have slivers of actual bygone realities in them. Others are entirely false. Nonetheless, the collective lore can be used to reveal important hidden truths about Harrison and his times. Like elusively shifting flames in a campfire, these mythical accounts hint at some greater understanding of days gone by, but then flicker away into the darkness of the disappearing past.

The enduring stories of Nathan Harrison are reflections of generations of people who told these accounts and the many audiences who continue to bear witness to such narratives. As author Tony Horwitz noted, “History is arbitrary, a collection of facts. Myths we choose, we create, we perpetuate… The [mythical] story may not be correct, but it transcends truth” (2008: 37). Lasting stories, such as the ones told of Harrison, result from a series of intricate performances that contain insights far beyond the original subject matter, narrator, or audience member. The collective lore can act as a prism of wisdom when observed from informed perspectives by bending and transforming singular understandings of the past into broader and better-contextualized knowledge.

Aside from being born enslaved in the early nineteenth-century American South and dying in San Diego as the region’s first African American homesteader, there are few incontrovertible historical facts of Harrison’s existence. The lone verifiable details of his life pale in comparison to the often deliberately sensationalized stories featuring his exploits. Truth rarely impedes the telling of an entertaining tale. Generations of narratives of Harrison’s adventures, eccentricities, and personal charms—told and retold long after his death—have grown his biography from a relatively obscure historical footnote into a captivating figure of local mythology. As such, Harrison’s legend has been far from static. The widespread tales of his origin story, his path to emancipation, and even his place in history have changed with great regularity in the century since his passing.

Nathan Harrison’s mixed legacy, until now, has been both as an untold and a mis-told account of American history. If it were not for the many tall tales, he likely would have been forgotten long ago. This book offers a new narrative of Harrison. It is informed by a critical reading of past records and accounts, broadened by an appreciation of multiple cultural perspectives, and most importantly, fueled by an entirely new data source of over 50,000 recently uncovered archaeological artifacts. These unearthed fragments from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries include the ordinary and the extraordinary. In the same deposit of everyday smoking pipes, sheep shears, and leather boot fragments, excavators found numerous ornate goods, including a stylish pocket watch, gaudy “President” suspender clips, and nickel-plated sock garters. We were even able to identify and pull a 100-year-old thumbprint off of one of the fired rifle cartridges uncovered at the site! This text is a study in history, anthropology, and archaeology; yet over the course of the analysis presented here, the reader will be drawn into discussions from a wealth of additional fields, including mathematics, chemistry, physics, biology, geology, architecture, literature, philosophy, performing arts, and many others. Insights from the sciences, social sciences, humanities, and arts all contribute to greater understandings of Nathan Harrison’s particular past and how people like him helped shape the present.