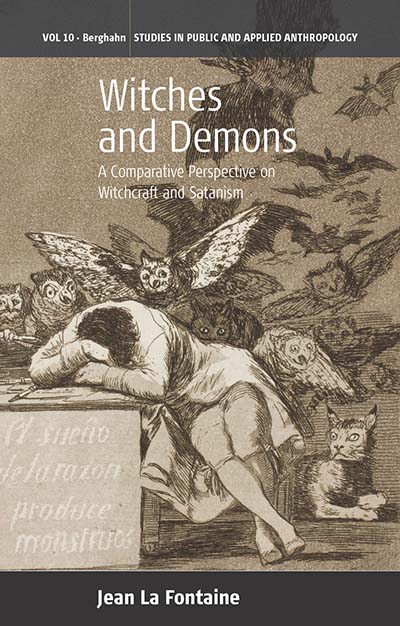

Jean La Fontaine’s Witches and Demons: A Comparative Perspective on Witchcraft and Satanism just enjoyed its seventh anniversary. And since it remains as popular – and as timely – as ever we asked Jean if she would take a look back at her Berghahn classic (available in paperback and eBook). So many thanks to Jean for this exclusive article.

Witches and Demons explores understanding of evil and the cultural forms that the understanding assumes. It looks at public scares about devil worship, misconceptions of human sacrifice, the use of body parts in magical practices and the recent accusations against children for practising witchcraft.

The articles concern modern forms of beliefs and actions that are also characteristic of earlier centuries; in some places the beliefs are still held. Witchcraft and sorcery were seen then as causing misfortunes, illness and, even, death, stemming from magical powers that were believed to be held by the people known as witches, or if all their powers were evil, as sorcerers.

The ideas about witchcraft therefore had an explanatory function in historic societies, including England. Inequalities of wealth and health, success and failure might be believed to be the result of witchcraft, used to promote success and make others fail or suffer misfortune. Historically, the accused were usually older women, often impoverished but thought to possess magical powers. They were believed to meet together to worship Satan and assist people who asked for (and will pay for) their help, either to attack their enemies, protect themselves or their children or to promote their own success. Children were believed to be lacking magical powers and thus unable to use the spiritual evil that witchcraft or sorcery entailed, although in rare cases they might be associated with their witch mothers in accusations as future evil-doers. In some cases in Europe, witches were believed to sacrifice babies to Satan at their meetings.

In Western or modernised societies today there are no longer many individuals believed to be either witches or sorcerers, but recently small groups of people worship the Christian devil, Satan, rather than the Christian God. There are similarities between the satanists(as they are called) and the wide-spread ideas of traditional witchcraft or sorcery but they are not identical. The witches of the European past were also believed to worship in their assemblies, known a covens; their evil powers were thought to derive from Him, through the evil spirits who were his followers and servants. However, unlike sorcerers who exercised “black” magic alone, witches might also possess powers to do good, to identify enemies, deal with illness or what today we might call ill luck. Such magicians might be suspected of an ability to harm as well as to heal, as a magician once told me. Since then, there have been changes, as the articles show, but the belief in witches’ magical power to cause misfortune is no longer associated with those who worship the devil today, even the most extreme of them. Nor can they heal as witches used to and did.

Ideas of witches and of their activities were not identical everywhere in Early Modern Europe, even at the time of witch-hunts in its many component societies. Nor are the modern versions the same as those of ancient beliefs, as historical research has shown. The development of science has established evidence supporting and proving the veracity of causes associated with many illnesses and misfortunes, that formerly might have been thought to be the result of ‘black’ magic exercised by witches or sorcerers. However, beliefs in witches and witchcraft have not disappeared in many other societies.

Human sacrifice may still be associated with devil-worshipping. However, a clear distinction between murders that are not associated with the devil, or any ritual that may be performed for Satan, can be made. Killing to provide ingredients for evil magic, undertaken by a magician for a client have been reported in parts of Africa and elsewhere. Such killing and the amputation of parts of the victim’s body to use as ingredients of powerful magic have been shown to be, not sacrifices that are performed for public good but as a means for an individual to acquire strong and evil powers. Human sacrifices make offerings to a god and where they took place in the past were normally part of rituals performed in public by priests and others who had acquired the appropriate ritual knowledge.

Beliefs in witchcraft are not fixed but have also been shown to be changing and to have changed over time. The Pentecostal and other evangelical Christians who have established Christian churches may not accept the existence of witches but they do believe that evil spirits, followers and servants of Satan, may endow his followers with the power to cause harm. These powers can only be countered by rituals that remove the spirit or spirits concerned. Exorcism (or deliverance as it is often called) by pastors of the churches concerned may be violent and may resemble in some ways the traditional attacks on those believed to be witches.

Such changes that can be shown to have occurred have not removed significant differences between the culture of morals in England and Europe as a whole and those of other societies where the existence of witches is still believed in. Traditionally, witches were identified within village communities, particularly of those whose behaviour was not considered normal or appropriate. Such actions can be seen to support morality in the local culture by discouraging action thought to identify witches. Among the more dispersed populations today, and in villages from which residents may leave to seek success, accusations may be made against kin or relations by marriage as they are the ones who are well-known to the accuser. Children accused of witchcraft may be accused of their parents or other close relatives. Many are identified by the pastors of churches, who may be paid to find the evil spirit and to cure its victim by exorcising it.

Modern societies may exist in violent conditions that encourage beliefs in their propagation through the use of magical evil. As anthropologists have discovered, understanding witchcraft requires the analysis of actions and the context in which they are set. They are not mere ideas.

Jean La Fontaine is Professor Emeritus at the London School of Economics, where she taught for nearly twenty years. She received her PhD from the University of Cambridge and has chaired the Association of Social Anthropologists, and served as President of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

A Comparative Perspective on Witchcraft and Satanism

156 pages, bibliog., index

Paperback, eBook, Hardback

Also available…

For the latest news on our books and journals please sign up for our email newsletters.